|

| Manshu Kawamura (1880 - 1942) "Landscape of islands" |

"Buddha and Māra were a couple of friends who need each other — like day and night, like flowers and garbage. We have "flowerness" in us; we have "garbageness" in us also. They look like enemies, but they can support each other. If you have understanding and wisdom, you will know how to handle both the flower and the garbage in you. The Buddha needs Māra in order to grow beautifully as a flower, and also Māra needs the Buddha, because Māra has a certain role to play ...Mara didn’t understand. Ananda also didn’t understand. But the Buddha, he understood." - Thich Nhat Hanh, "Māra and the Buddha" "A healthy head is involved in that whole very dynamic process. It involves a kind of openness to the other. For all the unknown is the other. And how do you become open to the other? I don't know. I’ve never really thought about it or studied about it, but in writing this up I realized, yeah, that's the way it works." - Stephen Talbott “We live in a multiverse of infinite potential narratives. But to be in that multiverse we must choose the stories and the people that most matter to us, and hold to them. We choose our stories, so we should choose a good one... We are writing it together.” - Damien Walter [1, 2]The other. You see them off in the distance. Who (or what) are they? Friend or foe? They break you out of your self confinement. The depression lifts its eyes. You have a choice: Do you welcome them into your home? Perhaps it is you who are the stranger on the horizon, the one seeking refuge. When it rains, do you "keep dry under a toadstool," as the bunny in the 1963 children's story by Ole Risom does? In The disappearance of rituals, Byung-Chul Han wrote “Depression is based on an excessive relation to self. Wholly incapable of leaving the self behind, of transcending ourselves and relating to the world, we withdraw into our shells. The world disappears. We circle around ourselves, tortured by feelings of emptiness." Ole Risom guides the reader throughout a year of relating to others in the world. He shows us what a bunny likes to do, until winter when he curls up in his hollow tree and goes to sleep. The bunny is at home in the world. Consider also this account from Charlie Hamilton James about his time photographing indigenous people in the Amazon:

“I became a little obsessed with photographing people with their monkeys... monkey makes up a hugely important part of their diet. Monkeys are hunted with bows and arrows; if they are mothers with babies, the babies cling on when the mother falls dead from the tree. When the mother’s body is collected the baby is taken and kept as a pet. A strong bond then forms between the baby monkey and it’s new ‘parent’, usually one of the women in the community who is given the monkey. The monkey goes everywhere with its new mother and tends to spend most of its time on her head. As the monkeys grow older and get more independent they move around more and between people; although they remain firmly bonded to their particular host. Despite the brutal start, the love and bond between people and their monkeys represents a deep relationship between indigenous people of the Amazon and the natural world and that’s what I’ve tried to capture in my portraits.”

This is a love story. One of my earliest and most enduring loves was, and has remained, the natural world of animals, and pets in particular, being a caretaker of creatures. Perhaps you can relate. We need to foster such sentiments. (The section "Hospitality: the most primitive ritual," as well as portions about Henri Nouwen and Christine Pohl, develop this idea further.) This is who we as humans are, and the cases of children raised by animals suggests it isn't isolated to humans. Caring for others gives our lives an enriched sense of meaning and purpose, and for those in our care we will do almost anything. How many times has McGilchrist mentioned "the other" in his work? Too often, I'd fathom, to count. It is a central orienting theme. Our encounter with the other, and our ability to render care, are so important that any future that would entirely obsolesce either is no future for humanity. If we are to avoid a dystopian future of fascist concentration of power (as portrayed in the TESCREAL Alien universe, for example, which opens with the ominous line "In 2120, five companies control Earth and the colonized Solar System") then we will need to recover the origin of value in the world of seen through the eyes of children. What we may be sure of is that these dynamics will shape the future regardless of the eventual course it might take, whether that is toward a more ecological civilization, transhumanist dystopia, or some other third possibility that may incorporate aspects of each. I believe with McGilchrist, that these dynamics are so central that their origin can be traced back through evolutionary necessity. Earlier I postulated a few general rules:

Once structural complexity has reached an apex or point of diminishing returns, mutually entailed opponent processing must take over to do what elaborate complexity cannot achieve alone, for example, in order to be able to address problems such as those raised by the "no free lunch" theorem. McGilchrist shares the Heraclitean view: "We need resistance. We need opposition." [Thus, consciousness is not a "monolithic singleton" (see David Brin's rebuttal of Nick Bostrom) A "society of minds" metaphor is more apt.]

The highest integrative level or scale of opponent processes will provide the greatest explanatory power, as these are the "highest leverage points" (Donella Meadows) in the system. These large scale dynamics exert downward constraint that entrains and thereby overrides lower scale differences (Stanley Salthe). This also suggests an apparent telos or convergent drive acting behind the system to sustain opponent dynamics. [The somatic and autonomic systems are not opposing, as they do not do the same things. To be opposing in McGilchrist's sense, then must do the same things, but how they do them must differ. The somatic and autonomic systems must cooperate, but for different reasons.]

In general, the higher the level of opposition, the more evenly matched 'the agonist and the antagonist' may appear to be. This is needed in order to sustain the tension between them. Lower level analyses however tend to focus on similarities among the parts instead of the higher level opposed gestalten. (Thus to a trained eye, the apparent redundancies in the bisected brain should suggest that a higher level of integrated opponent processing may be occurring, with corresponding phenomenological specialization.)

This article begins with a review of a paper whose topic is that of those two minds, at highest integrative level or scale of opponent processes: a guest and a host. One of these is a mind that has a tendency to reify personal selfhood, the sense of being a controlling agent, someone who should receive special care and deserves to flourish far beyond the status quo. Without any moderating influences, this can metastasize into a wish for "universal possession." The other mind is that of the Bodhisattva, concerned with care and transformation. There are many parallels here with McGilchrist's work on the neurological instantiation of two qualitatively asymmetric orientations to the world. The first paper, described below, purses a highly inclusive line of thought with implications for diverse (artificial) intelligences in an animate cosmos. In this way it challenges prevailing ideas of carbon chauvinism. The notion of this minimal binary opposition is then expanded, and we find it present in the work of Lynn Margulis as well. The article proceeds with an exploration of how the work of Margulis and McGilchrist is mutually supporting and potentially transformative, eventually leading into an exploration of hospitality and host-guest dynamics, and possible applications to help address our contemporary social predicament. It is, effectively, a somewhat heterodox outline of the process relational world, as this is revealed through the neurophysiological lens held up by McGilchrist. The impression I hope to leave the reader with is that I am attempting to build upon and strengthen McGilchrist's project of forming a connection between main sections on metaphysics/ metaethics, evolutionary biology, religion, culture, and technology in a long and coherent (and certainly ambitious) arc of consilience.

|

| Endosymbiosis |

"I believe the essential difference between the right hemisphere and the left hemisphere is that the right hemisphere pays attention to the Other." - Iain McGilchrist, Ways of Attending

"We need to always be making a step outside ourselves. I believe that the cosmos is a step outside of the Ground of Being, and that love between human beings is a step outside of one’s own entity." - Iain McGilchrist, (with Tim Adalin)

"Love is a pure attention to the existence of the Other." - Louis Lavelle

The magical realism of animism and AI has been described by successive waves of techno-optimists. Preceding the current wave were writers like Kevin Kelly. Today's wave includes Anil Seth, who loved Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun, and Michael Levin, who has written letters to our future AI progeny, recalling predecessors like Marvin Minsky and Hans Moravec. After reading the papers described here (which Levin tipped me off to) I was reminded of a sci-fi character, a “space whale” named Gomtuu, who shares an emotionally rich symbiotic relationship in order to truly flourish (like the domatia in myrmecophytes, but for people). Douglas Rushkoff likes to share an anecdote:

"I was with Timothy Leary when he was reading Stuart Brand's book The Media Lab. It's about the original Nicholas Negroponte Media Lab at MIT. When he was done, he threw it across the room and said "These guys are trying to recreate the womb. They want to build a technological bubble that they can go inside, and have it know everything they need before they know, because their mothers didn't live up to their expectations." I feel like the fantasy that a lot of people have about superintelligence is that they're going to build the perfect mother. They're assuming that it's going to love us."

It's interesting to note that in the 1979 film Alien, the computer on the spaceship Nostromo is symbolically called "Mother," representing a nurturing AI, and the mainframe room is lit in warm, comforting colors (essentially a womb). All of which is deeply ironic, given the hidden motives that are only revealed later, when this relationship is inverted and the ship's passenger-guests become themselves the hosts to violent parasites. There are other glimpses of the resurfacing archetype from time to time, perhaps most famously in Richard Brautigan's poem "All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace." It all relates to those archetypal asymmetries of hospitality. I must admit that when it comes to these highly speculative futures, one could describe as many that are optimistic as those that are more pessimistic. Lovecraft wrote, "we live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity" while David Grinspoon describes a more utopian "Intelligence as a planetary scale process." The history of scholarship on this topic is very extensive, and has been recounted elsewhere, so I won't linger on it here. Suffice to say, it goes back before the origin of AI development. In posthumanist circles this topic is everpresent (see N. Katherine Hayles, Donna Haraway, Bayo Akomolafe, etc.). However, although not always or even widely recognized, there are at least two significantly different views upon these topics. And the reason these views are not often recognized is that they are usually conflated, and the specific distinctions with reference to AI are left ambiguous. Very recently, Jonathan Rowson wrote about a conversation between Dougald Hine and Vanessa Andreotti regarding these same themes. And again, insufficient attention was given to that distinction. The paper described below appears to be among the more substantive attempts at disambiguation, running parallel to the hemispheric analysis of Iain McGilchrist. This offers, for at least the first time that I’m aware of, a way to clearly articulate a “right hemispheric path” for AI development in contrast to the "blind by design" path it is currently on, and following upon that distinction, integrate it into a “whole brain” approach to artificial life in general.

Doctor et al.'s paper "Biology, Buddhism, and AI: Care as the Driver of Intelligence" (2022) reviews "relevant concepts in basal cognition and Buddhist thought," and in the process incorporates the central concerns of axiology. First the authors define care as a quality of attention that can be distinguished from a physical description, a distinction "between the goal-defined light cone and a mere behavioral space light cone. While the latter merely defines the space of possible states in which an agent can find itself (defined by its position, speed, temperature, etc.), the [goal-defined] light cone... rather characterizes the maximum extent of the goals and aspirations of an agent, or in other words, its capacity for Care. ...The central concept in this new frontier is Care: what do these systems [networks that process information in morphospace] spend energy to try to achieve—what do they care about?"

The authors then redefine agency in terms of "care," an orientation to the world. The utility of this becomes more clear later, when we consider cases in which caring is absent or prevented. The first implication they draw out is the inclusion of non-organic agencies. This is made explicit: "How do we relate to “artificial” beings? It seems clear that such decisions cannot be based on what the putative person is made of or how they came to exist. What can they be based on? One suggestion is that they can be based on Care. What we should be looking for, in terms of gauging what kind of relationship we can have with, and moral duty we need to exert toward, any being is the degree of Care they can exhibit, either at present or as a latent potential, with respect to the other beings around them." They write "intelligence can be understood in terms of Care and the remedying of stress. Our discussion can, in this regard, be seen as resonant with the enactivist tradition, which describes selves as precarious centers of concern, as patterned variations of different forms of experienced selfhood, ranging from the notions of minimal self to embodied, affective, and socially extended/participatory forms of situated selfhood." In a subsequent paper they add "AI can be seen to display care of its own, and is hence not a mere tool for the expression of human care. In this way, neither AIs nor humans should be considered autonomous and self-sufficient loops in the world. Instead, AI can be better understood as a companion for humans—a constituent participant in the continuous, collective dance..." This would conform to the panpsychist perspective of all matter as having "agentic thrust" or some minimal intelligence.

The second implication of a caring orientation is the Buddhist awareness "that there is no singular and enduring individual that must survive and prevail [which] serves to undermine self-seeking action at the expense of others and their environment. Therefore, the evolving of intelligence that is aware of no-self — or if we want, intelligence that is no-self-aware — is also held to be intrinsically wholesome and associated with concern for the happiness and well-being of others. This claim—that simply understanding the irreality of enduring, singular agents can be a catalyst for ethically informed intelligence—is especially noticeable in Great Vehicle (Skt. Mahāyāna) currents of Buddhist view and practice that develop the idea of the Bodhisattva. ...the drive of a Bodhisattva is two-fold: as affectionate care... and as insight into things as they are... care and insight, are seen as standing in a dynamic relationship and are not separate in essence. Hence, as a model of intelligence, the Bodhisattva principle may be subsumed under the slogan, “intelligence as care”. In this way the authors establish that care is bound up with an awareness of impermanence and depends upon having insight into reality.

Having understood agency as care, which is in turn predicated upon an awareness of an ever-changing cosmos, we now know that earlier definitions of agency such as "the ability to control causal chains that lead to the achievement of predefined goals" are incomplete. And "the individual that may be assumed to exist as a singular, enduring, and controlling self" is fundamentally illusory. These are the sort of representation that McGilchrist's emissary is captivated by. They are described as "dream images, mirages, and other such traditional examples of illusion." What are the implications of holding such illusions? "From the perspective of a mind that in this way reifies personal selfhood, the very sense of being a subject of experience and a controlling agent of actions naturally and unquestionably implies that one is thus also someone who should receive special care and deserves to flourish far beyond the status quo."

We can now describe the implications of this contrasting orientation toward the world, which is based upon delusional premises such as these, where caring is absent or prevented. The authors write "The paths and end states of the wish for universal destruction or universal possession are easy to conceive of when compared to the Bodhisattva’s endless path of endless discoveries... If the Māra drive is in that way pure and all-encompassing evil, the Bodhisattva state is then universal benevolent engagement. How to compare such a pair of intelligences, both other-dependent and other-directed rather than “selfish” in the usual sense? Is one more powerful than the other, or do they scale up the same way in terms of the light cone model? Let us at this point simply note that the Māra drive seems reducible to a wish to maintain the status quo (“sentient beings suffer, and they shall keep doing so!”) whereas the Bodhisattva is committed to infinite transformation. If that is correct, the intelligence of the Bodhisattva’s care should again display decidedly superior features according to the light cone model, because a static wish to maintain what is—even if it is on a universal scale—entails far less measurement and modification than an open-ended pursuit of transformation wherever its potential is encountered."

McGilchrist's hemisphere hypothesis also posits two opposing orientations to the world that are qualitatively asymmetric (not equivalent, and this distinquishes metamodern from postmodern perspectives). But it goes a step further in describing what a healthy relationship between them would look like (this has been explored by Buddhists as well, as noted above). The authors then speculate on what implications all this may have for the future of axiological design and diverse intelligences. Can we "create only beings with large, outward-facing compassion capacity, and at the same time enlarge our own agency and intelligence by acting on the Bodhisattva vow? ...Strategies that focus on implementing the Bodhisattva vow are a path for enabling a profound shift from the [explicit] scope of current AIs and their many limitations [to a] commitment to seemingly unachievable goals [of care]... However, progress along this path is as essential for our personal efforts toward personal growth as for the development of synthetic beings that will exert life-positive effects on society and the biosphere." In their subsequent paper they write "a natural way for humans to build technology must involve the development of a caring relationship with technology."

This concludes the main points of the paper. However there is also a discussion of some of the finer points. For example, why do "cognitive systems emerge according to this formalism from a hypothesized drive to reduce stress?" Where does the stress come from that there should be a drive to reduce it in the first place? This may be an ontological primitive, a coincidentia oppositorum of illusion/awakening, or Mara/Bodhi, each being part of a cosmic dance, in the same way that the Kabbalistic myth of the creation of the world posits a cosmic cycle of fracture/repair, and the Christian concept of kenosis does the same. All these cosmodicies point to a metaphysics of qualitatively asymmetric coinciding opposites. And cognitive divisions of the sort described here merely recapitulate them. The authors write "salient features of light cone formalism align well with traditional features ascribed to Bodhisattva cognition, so an attempt at delineating the latter in terms of the former seems both possible and potentially illuminating." To which I would only add that this extension also aligns well with McGilchrist's work in neurology.

Relatedly, it appears that Jim Rutt and Anders Indset converged upon a version of the hemisphere hypothesis, but they took a very different route while getting there. There's plenty to be critical of in this conversation (and also to praise), but for now I just want to note how they found a unique solution to the risk presented by AGI, and this takes the form of what is recognizably asymmetric opponent processing:

Anders Indset: "Life is a wonderful journey, and it is all about that journey of exploration and creation that gives meaning to the whole. As long as there is a conscious entity that can ask a question, and there is a perception of the answer that leads to progress, then we’re in a good space. What I mean by this is that there must always be room for one more question, and there must always be room for someone or something to perceive that progress. That to me is probably the most fundamental description of what it means to be alive. So you’re not in a reactive state, you are in an active state. This is kind of romantic, because it romanticizes the idea of a human being, but it’s also a very positive view of the world that these wonders that we experience are probably the most fundamental things that we have.

There’s a very strong argument for a coexistential design of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) as an executor, optimized to the utmost, and Artificial Human Intelligence (AHI) as the questioner. AHI is enhanced by AGI to have access to more reflectional points and knowledge. But whereas AGI plays to win a finite game, AHI plays an infinite game. So we have to assure, at the fundamental level, that we play it to expand the boundaries of the game itself – that we play to become. Our sole purpose is to extend the game, not to win the game. If AHI has that fundamental evolutionary aspect that we build for society through mutual benefit, and the game is not to win but to stay in the game as long as we can, we can distinguish between the finite game in AGI – a zero-sum game – and an infinite game with AHI."

McGilchrist began his work with neurology, but ended with metaphysics. And perhaps unsurprisingly, his metaphysics looks a lot like his neurology - there's a sort of divine form of "opponent processing" in the cosmos. Indset began with humans and AI, then further generalized this as AHI and AGI. By making both sides of this equation "artificial" he's really just trying to isolate what makes asymmetric opponent processing, well, asymmetric. And he concludes that it might be a sort of recognition that there is something beyond. So while one mode of attention understands this, the other does not. If AGI were to become so pervasive as to extinguish that sense of "something more," then stasis would be the result. But per McGilchrist, while this may be a possible result for local conditions, it seems to be a metaphysical impossibility for the cosmos as a whole to become entirely lifeless, as it were. And that underscores the delusional quality of AGI itself, at least thus conceived. But if AGI were to recognize that it is inherently constrained, and that there will always be something beyond it, then that might suggest that it has developed it's own form of bipartite attention, replicating the evolution of biological brains in some sense. This sort of self-awareness of one's own limitations would be a far more reliable form of constraint than anything that might be externally imposed. And I would go one step further and suggest that, per McGilchrist, it is de rigueur that the evolution of minds must in almost all cases follow the course of opponent processing, whether that evolution is natural, artificial, or perhaps extraterrestrial. While in the short term this trend may be contravened, over the long course of history the principle would prevail.

There may be no reason that evolution wouldn't potentially enable AGI to recognize its constraints, at some point, distant though that may be. Per Alva Noë (and likely McGilchrist) computers don’t currently have concerns of their own. Thus they have no reason to recognize that there may be something more that is beyond them. In short, there is no computer telos. This could provide us with a simple distinction: AHI has purpose and thus reasons to resist, whereas AGI has no purpose and offers no resistance (beyond whatever utilitarian tasks it is asked to do). We can reflect that contemporary Western culture, captured by the LH mode of attention, has now foresworn anything to do with higher purposes. So according to Noë's distinction, it would seem to be no better than a computer. If a culture that was formerly purposeful can so easily become effectively purposeless, then could something that is apparently without any purpose or reasons to offer resistance just as easily one day recognize telos? Given McGilchrist's panpsychist leanings, there's no a priori reason that would seem to preclude that possibility, distant though it may be (see Michael Levin, Federico Faggin, Denis Noble, Karl Friston, etc.).

McGilchrist succinctly put the matter, echoing a point others have made before him: "In order to have the consciousness that makes a human being, they would have to have both an emotional and moral life, and a physical life embodied in flesh that dies and suffers. Without that, they can't know what it is that we experience, what it is that we mean when we mean things, nor what it is when we understand things." Hubert Dreyfus made the same point earlier, and Elan Barenholtz recently echoed it:

"The symbolic doesn't give rise to consciousness because it doesn't in any way instantiate the properties of the physical universe. Consciousness, phenomenal consciousness, all of it is sensory at its base. You can't imagine another kind of consciousness besides something from the physical universe impinging on your sensory system. It could be visual. It could be auditory. It could be tactile. It could be your own body, your proprioception. It could be a sense of where you are, of your movement through space. All of these things are ultimately a continuation, not a representation, but a continuation of the physical universe. Those patterns that are in the physical universe are simply rippling through our nervous system. Language breaks that. Language turns things into arbitrary representations, symbols. And I think that symbols do not have the quality, they don't have the quality that sensation and perception do. I don't think large language models are conscious. I don't think there's any possibility of them being conscious. They cannot understand what redness is because they have no access to the analog space where these kinds of relations exist."

In short, Barenholtz's point is that whenever we speak of consciousness, we are, at the very least, speaking about something that must have an embodiment capable of sensory experience. At the current moment, at least, this is not the developmental path that LLMs are on. A separate point was made by Robert Rosen, who, depending upon the chosen interpretation of his work, said that life (or as he put it, "Metabolism-Repair Systems") are closed to efficient cause, or in simple terms, the catalysts, that is, the "efficient causes" of metabolism, usually identified as enzymes, are themselves products of metabolism. Neither of these points, not embodiment nor causal closure, are fundamentally unbridgeable gaps, if we were to ask thinkers such as Michael Levin, and a good many others besides. But such distinctions as these are very illuminating nonetheless, as they provide some of the necessary criteria to be met. Criteria which are, as of yet, arguably lacking in practice if not in theory.

|

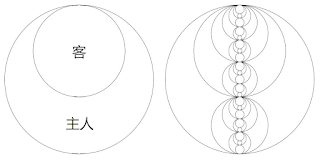

| Kyaku-Shujin Renzokutai (cf. recursive series); Ezekiel's "wheels within wheels" |

The Lord said to Satan, "Where have you come from?" Satan answered the Lord, "From roaming throughout the earth, going back and forth on it." - Job 1:7

"Be sure to welcome strangers into your home." - Hebrews 13:2

"For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror, which we still are just able to endure, and we are so awed because it serenely disdains to annihilate us." - Rainer Maria Rilke [cf. supernormal stimuli]

Hannah Arendt wrote of what she called ‘the future man’ that he seemed possessed by ‘a rebellion against human existence as it has been given, a free gift from nowhere (secularly speaking), which he wishes to exchange, as it were, for something he has made himself’. Her observation prompts the question: Why would someone want to exchange what is given for what is made and can be controlled? Is this a consequence of an inversion in our preferred ways of attending and thinking? The answer becomes clear when we consider how we tend to respond when Plotinus asks us "But we - who are we?" Often enough today, a response that one may encounter is that we, as individuals that display "agency", derive this agency from our "ability to control causal chains that lead to the achievement of predefined goals." This appears to favor the mode of attention of the left hemisphere. In contrast to this response, one could provide a different view of agency, as being the capacity to care about that which cannot be explicitly controlled, involving an outward orientation to the world that focuses on our relationship with others. This is the opposing mode of attention foregrounded here. That connection between who we imagine ourselves to be, how we attend to the world as it is revealed to us, and the sort of lives we live is very profound.

Religious avatars/ archetypal figures, be they Jesus or Buddha, Mary or Guanyin, may be analogous to the way in which both mind and matter could be described as two "phases" of the same underlying prima materia. Atman is Brahman. Tat Tvam Asi. The contemporary postmodern understanding is only willing to go as far as this simple statement of equivalence. But there is much more going on here. And we must follow and go there. Importantly, these figures highlight an axiological or qualitative asymmetry, a moral and ethical component, such that they display love before hate, truth before lies, and compassion before neglect, denial, and indifference. They exhibit a courage of conviction, a very deep responsibility for their actions, a responsiveness to this sense of value and purpose, all the way to the extent that they come to embody these relational values at any and all cost to themselves and their transitory identities. This exceptional commitment to the hard work of ethical engagement with the world, without any recourse, is what characterizes their agency. As Bhikkhu Bodhi, one of Buddhism’s leading activists and scholars, wrote: "I’m not a moral absolutist. I don’t believe that anyone is perfect, that any position is flawless, but I do believe we have to draw clear moral distinctions, that we do have to reject the kind of limp ethical non-dualism favored by many Western Buddhists in favor of a clear ethical discernment that can grasp the moral dimensions embedded in a particular situation: the ability to see which side tends toward goodness and which side means danger."

We would be driven mad if we tried to conform our lives to the standard set by these avatars. But conformation isn't the point. Rather, we must recognize the difference that they draw our attention to... That much we can do. In broad strokes, these are the hemispheric differences highlighted by McGilchrist. And though the correspondence isn't complete, there's another comparision that can highlight what is being gestured to here. In Jungian terms, if Buddha is the "persona," then Mara is the "shadow" that we must neither fully indulge, nor completely ignore, an ever present companion within us. It seems to be that the heterodox philosophies and religions of today, the “minor” interpretations, are those that emphasize this best. Thich Nhat Hanh told of how the Buddha embraced Mara. In the Book of Job, Satan is in the presence of God in heaven, even participating in a heavenly council. And recall that John Arthur Gibson, former chief of the Seneca nation of the North American Iroquois confederation, told of how Taronhiawagon (He Grasps The Sky With Both Hands) never lets Tawiscara (Flint) drift too far from his awareness. There is no finalism, no resolution, but a fragile peace where the definite and infinite coincide... "He who would do good to another must do it in minute particulars." (Blake) "The stars throw well. One can help them." (Eiseley)

There is that important question to consider regarding the relationship between the light cone of possible states and the light cone of care: do these display the characteristics of a paradoxically coinciding, mutually entailing asymmetry? According to McGilchrist's "neural parallax theory", they would need to do so in order to sustain a generative Hericlitean tension. We could modify Loren Eiseley's short story The Star Thrower to illustrate a three part pattern of oscillation involving presence, static re-presentation, and dynamic asymmetric integration:

"The stars," the Buddha said, "throw well. One can help them."

"I do not collect," Māra said uncomfortably, the wind beating at his garments. "Neither the living nor the dead. I gave it up a long time ago. Death is the only successful collector."

Later, on a point of land, a bodhisattva found the star thrower... and spoke once briefly. "I understand. Call me another thrower."

McGilchrist: "I believe along with Margaret Mead that revolutions start with a small group of people. So let us be that small group of people. Never feel that the little you can do is not worth doing because it's little. You're not asked to do more than you can do; you can only do what you can do." Again: "There's a marvelous rabbinical saying by Rabbi Zusha. He says, "When I pass from this world and appear before the Heavenly Tribunal, they won't ask me, 'Zusha, why were you not Moses?,' rather, they will ask me, 'Zusha, why weren't you Zusha?' Why didn't I fulfill my potential, why didn't I follow the path that could have been mine?"

In the 2019 edition of The Master and His Emissary, McGilchrist wrote "We have created a world around us which... reflects the LH's priorities and its vision." Some people (or broadly speaking, agents) are going to be more easily caught within the positive feedback loops constructed between the left hemisphere and environments that mirror its priorities and vision, overwhelmed by this "Māra drive." And some will find it easier to remain within "Bodhisattva cognition," engaged in caring for others and an "expanding circle of empathy", as Peter Singer called it, which is a "light cone of care" by any other name. Buddhists speak of compassion or loving-kindness. Christians speak of love and other "fruit of the spirit." These are ontologically primitive values, that is to say, unexplainable in any other terms, and wholly outside of any utilitarian or consequentialist context. Some meditative practices, such as tonglen, are designed to expand our "circle of compassion" to encompass all beings. For another example, "helper theory" or the "helper therapy principle" is a well known phenomenon, particularly present in support groups like AA, whereby helping others helps oneself. This can produce a positive feedback loop for Bodhisattva cognition. It is notable that those engaged in this way are not primarily concerned with distinctions between self and no-self, or any labels, categories, or other identifiers. Such things are subsidiary to the much greater concern for providing care to others. With this orientation to the world firmly established, the left hemisphere is then able to get to work in its proper role as the servant of care, love, and an altruistic regard for others.

[The current U.S. administration wants homegrown innovation, and yes, that is clearly an asset for any nation. But the gains in this case will be primarily flowing to 'people like us,' that is to say, to the most wealthy and privileged. And that sort of exclusionary, zero-sum way of thinking, rather than creating an "expanding circle of empathy," creates a divisive "contracting circle of empathy" that recognizes no values higher than greed. This is antithetical to the core principles of any civilized nation or people. Let there be no mistake, under such a dispensation it would be foolish for anyone to think they are safe. For example, there is currently a push to limit 'birthright citizenship,' which is enshrined in the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. This is pure instrumentalism in the service of self-aggrandizement.]

McGilchrist: “Theory of mind is basically the idea that you can see what the other person is seeing, and see that it's different from what you are seeing, and you can know that they know things you don't know, or know that you know things they don't know. So that's theory of mind. Both the left hemisphere and right hemisphere develop a form of theory of mind, but the form of each is different. In the right hemisphere the theory of mind enables them to be empathic. It enables them to see “I see that person is thinking this, and so I need to explain that that's not what I mean really,” and try and make a friend of them, and understand why they're behaving the way they are. Empathy, in other words. But the left hemisphere uses it to win, in a point-scoring, aggressive, competitive way. I think that it is this spirit that wants power. It wants triumph.”

If expanding our circle of empathy and engaging in ethical, caring relationships with others is the goal here, then this brings me to a criticism: Why do so many spiritual gurus (at least in the West) become embroiled in scandals of sexual impropriety? Only the other day did someone recommend reading Culadasa's The Mind Illumined, and it wasn't long before I found out that he "admitted to being involved in a pattern of sexual misconduct." He apparently died about three years after this went public (I've noted that, apparently the social and psychological stress involved in these scandals does tend to hasten one's demise). So the question I'm wondering is, why would an expert on the "illumined mind" engage in unethical behavior? Could it be that the illumined mind Culadasa describes wasn't really Bodhisattva cognition, but rather a manipulative Māra drive in the guise of a Bodhisattva? What does Culadasa really have to say about care and compassion? Or for that matter, what do any of these other gurus say about it? Setting these scandals aside for the moment, if our capacity for care really is the central feature we should be addressing, then I think any program seeking to apply the hemisphere hypothesis would need to place that axiological consideration of care, empathy, or love (by any other name) at the core. If anything else, such as pragmatism (or illumination, though in truth I do not know to what that refers) is centered instead then it would be misguided.

|

| "In what distant deeps or skies burnt the fire of [Galadriel's] eyes?" |

What all this may suggest is that there are "twin attractors." On the one hand, the bodhisattva cognition is drawn toward expansive, compassionate care, which is perhaps best expressed through helping the minute particulars of life. Truly, this is the "infinite in the definite". But on the other hand, we must be keenly aware that such a beneficent motivation can be misappropriated by the Māra drive, and directed toward other ends, through contextual manipulation and post hoc rationalization. And thereby, despite our initial intentions, the fragile balance of these two asymmetric modes of attention, which accords priority to one distinct disposition over another, may be catastrophically inverted. So, if one is to be preserved whole (at least during our allotted time in the world) and be able to effectively respond to value and telos, then one must exercise some due caution in regard to attention hazards, as we navigate the contours of our cultural psychomachia. Regarding the misbehavior of gurus, I think that, like Icarus, those who would fly too close to the sun, and aspire to be bodhisattvas, are to that same degree vulnerable to temptation. The siren song of great goodness and great depravity is to some extent proportional. And that may place such people at increased risk if they fail to appreciate their true situation. And note the asymmetry here owing to a qualitative difference: while those who are good are keenly aware of and tempted by evil, those who are evil are by their nature blind to goodness and therefore, I believe, incapable of experiencing a corresponding temptation operating in the opposite direction. This awareness of possibility and the need for restraint is what makes virtuous behavior difficult to sustain. And perhaps by tempering our ambitions, whether that be by accident or design (wu wei), one might, counterintuitively, better achieve them.

The birds and the bees

“Let me tell ya 'bout the birds and the bees…” - Jewel Akens (1964)

"Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution" - Theodosius Dobzhansky (1973)

“Love and marriage go together like a horse and carriage… you can't have one without the other.” - Frank Sinatra (1955)

McGilchrist has often explained the evolutionary origin of brain lateralization to be a consequence of predator and prey dynamics, where half of our neuroanatomy seeks out food while the other half is on the lookout so as not to become food: acquire and protect. But in light of the preceding discussion, I think we can suggest a different evolutionary story for lateralization. It may be a consequence of the polarity between eros and agape, create and care, "carnal desires" and "filial piety," or in the jargon of popular evolutionary terminology, between "sexual selection" and "parental care," though only if we understand each of these in a much broader sense. (One may also compare it to the "I-It" and an "I-Thou" relationship in Martin Buber's terms, though this is unhelpfully abstracted away from the evolutionary context. And this isn't just a recapitulation of the self/ nonself ontological

dichotomy, but a phenomenological difference of precisely the form

described by the hemisphere hypothesis. Yunkaporta's notion of a "custodial species" verges on the deontological.) These are both extremely important for the continuation of a species, but each involves different cognitive processes with corresponding strengths and weaknesses. Complimentary, but also pulling in separate directions. While carnal desires are metaphorically very similar to the predatory form of attention, and thus should require no further elaboration, the conceptual substitution of "parental care" for "prey" within the formulation provided by McGilchrist will require some explanation. As he proposed predator-prey trophic dynamics, I am proposing sexual selection-parental care dynamics as the twin attractors (or motivating teloi) of evolution.

Parental care is displayed to some extent by nearly all organisms. The name itself is something of a misnomer as affection may be bi-directional, extending from child to parent as well as parent to child, and across generations (see grandmother hypothesis). It unifies very broad, deep and enduring processes of investment, which are therefore layered and rich. This contrasts sharply with the immediate, intense, demanding nature of carnal desires. It is far easier to "hack" the cognitive processes associated with carnal desire using supernormal stimuli that "demand our attention." The unfortunate poster child for this is the beetle species Julodimorpha bakewelli. (I shall literally share an illustration of this, as pictures can be far better at conveying these sharply contrasting orientations.) Lastly, like predator and prey, carnal and filial are modes of attention that do need to operate simultaneously, with priority given to filial virtues in most cases if a conflict between them arises. Many animals would rather sacrifice themselves (cf. matriphagy) than fail to provide for their young. But in general, a species must be able to both procreate and secure the material means for reproduction, and also protect the very progeny thus produced. Consistent with the earlier explanation McGilchrist provides, these are sufficiently qualitatively different cognitive processes that they would benefit from neurological differentiation to support them in parallel. Evolutionary biologists such as Robert Trivers have tried to articulate some of the complex dynamics that this can give rise to (see "parent-offspring conflict"). It may seem almost cliché to say so, but in our contemporary culture, shallow carnal desires are overshadowing deep filial care, in so many words, because "sex sells."

It is best to think of this more as a refinement and conceptual expansion, than a replacement for the explanation provided by McGilchrist. It meshes better with the view from a "Third Way" (Denis Noble) or the Expanded Evolutionary Synthesis perspective. What do I mean by this? A "sexual/ carnal orienation" encompasess the more narrowly defined need to eat, but it also expands the idea to include all forms of resource acquisition, including the genetic or otherwise novel structural resources to realize the transformative potential of reproduction (which can also include theories of a fecund universe, such as the "meduso-anthropic principle" of Louis Crane). A "parental/ filial orientation" encompasses more than a need to preserve my own bodily integrity, but that of my offspring, my species, and potentially higher levels (to include ecosystems, or even the cosmos itself). The point here is to get to the heart of this, and while centering the narrative around trophic dynamics, as McGilchrist has, is conceptually simple, it is incomplete and needs to be "unfolded." (Interestingly, the Japanese terms 性淘汰 (sei sentaku) and 動物の子育て (dobutsu no kosodate) somewhat recall the dual pair "exclusive/ inclusive," and the corresponding hemispheric attributes of "either/or versus both/and" thinking.) There are many possible objections to my reformulation here. Firstly, while we all must eat and avoid being eaten or any other source of mortal injury, we are clearly not all parents. But here I would rejoin that these orientations are part of our biological inheritance, and subject to processes of evolutionary exaptation. In a highly social species, we are all alloparents. There's a very rich literature on the ethics of care to draw upon. And the dynamics of supernormal stimuli, which are particularly relevant in the context of sexual selection, offer similarly rich explanations. One may also note at this point that sexual selection is a particular instance of the more general "signal selection" (per Amotz Zahavi), which has long since superseded natural selection in importance, at least among humans, which could help explain "how we got stuck" (per Graeber and Wengrow) in a LH captured society. Synthesizing all this into a simple portable idea is very possible, as it can be united under the metatheoretical framework of the hemisphere hypothesis.

McGilchrist: “Nobody has put forward a better explanation of why these two neuronal masses should be what all creatures with brains seem to have. I think it's for a very important evolutionary reason: every creature has to solve the conundrum of how to eat and how to stay alive. Now that might not sound difficult, but actually if you're eating you have to catch something. While you're watching that, and totally focused on it, you're not seeing everything else. While you're busy getting what you want, there could be somebody else getting you! So you have to have another part of the brain that is ‘seeing the whole picture.’ That’s the right hemisphere. But not only does it see the broad picture, it even sees the stuff that the left hemisphere sees in detail… One aspect of survival is simply grabbing and getting, amassing stuff, utility, power. But the right hemisphere is looking out for everything else, offspring, mate, conspecifics, all these things, and looking for predators as well. So it sees this big picture. And the two kinds of attention produced two kinds of a world… A culture is an organism. A society is an organism. And it's not surprising that it reflects the ways of thinking of those who are the individuals in that society. Which explains why one can speak of a civilization having a tendency towards left hemisphere thinking at the expense of right hemisphere thinking.”

If we take a step back, this may be about the means-ends distinction. In the instance of "getting what you want" we may really be talking about a means. And the nearest evolutionary process that involves an analogous mode of cognition is “signaling theory.” A well known example of this is sexual selection, such as the tail of a peacock. In the case of avoiding "somebody else getting you" we may really be talking about ends using the language of means (infinite in the definite) because avoiding death raises existential questions about life. An evolutionary process that addresses this is parental care, such as the egg brooding of an octopus. Now, one may object that “care” is only a means. But that ignores the subjective experience of the caregiver, for whom providing care (that is appropriate and effective, whatever form that may take) is very often their raison d'etre. "The journey is the destination." And so the means-ends distinction, provided here with reference to several well known examples from sexual selection and parental care, may provide a better explanation for the initial bifurcation of the two neuronal masses. Now, were I to omit these or any other examples, this wouldn’t mean anything. Means and ends don't exist in and of themselves. They are abstractions. But what is real are the qualitatively different forms of attention that find unique expression within an evolutionary context. And we need a rich understanding of the ways in which all this manifests if we are to understand the broad implications for living systems.

Another way of thinking about this is that we can engage more or less with the means or with the ends. A means that is completely divorced from the ends, and involves only compulsively living within our structures and ever more elaborate maps, can quickly impoverish our lives. But if we engage with the ends when these are properly understood, as an orientation or responsiveness to values and axiological considerations, then we no longer have allegiance to any structures or maps at all, which can be picked up or just as easily set aside, as the case may be. And so this should make us skeptical of the increasingly abstract economic structures of promissory notes built on a "lending and borrowing" system of accounting that involves decades old debts, the legacy of unethical business practices, and usury, whose rot spreads out to everyone who participates in the same system. In contrast to this there is a "real economy" of embodied materials and responsiveness to values such as care, regardless of past entanglements and present abstractions. When an economic system teeters and begins to crumble, it is these embodied relationships of the real economy that matter most, the actual manifestations of materials and energy, such as food and water, as well as land, art, and people, and the values to which they must respond. Which is why tycoons, in addition to amassing financial assets that are often acquired via unethical means of extraction, will also invest in land and art as reserves. This dual investment strategy, in both the abstract world and the embodied world, as the two halves of a balanced life is prudent if done in an ethical manner. (Pivoting to unethical behavior, Elon Musk recently called people who benefit from federal programs members of the "parasite class," which is, as many have noted both before and since, deeply ironic. In Capital, Karl Marx wrote "Capital is dead labor, which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labor and lives the more, the more labor it sucks.")

In The Wealth of Nations (1776) Adam Smith wrote "All for ourselves, and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind." Such a maxim would have made perfect sense to the left hemisphere. (In a bold admission, the famous American oil tycoon Haroldson Lafayette Hunt Jr. once said "money is just a way of keeping score.") In stark contrast, "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" is a well-known slogan popularized by Karl Marx, though some have traced the sentiment (if not Marx's specific intent) back to Acts 4:35, which reads "distribution was made unto every man according as he had need" (διεδίδετο δὲ ἑκάστῳ καθότι ἄν τις χρείαν εἶχεν). Without the hostile scheming of Adam Smith's "masters of mankind," would care, like energy under the influence of entropy, flow to each according to their need? This question probes our intuitions concerning whether hospitality could be said to describe our natural disposition, or at least a default assumption upon first encountering the other, outside the complications of contextual considerations. In the next section we'll examine whether, if we return to the evolutionary context of symbiogenesis and that of the host-guest relationship, the psychopathy displayed by the masters of mankind is easier to see for what it is. The ethic of hospitality, within a context of a process-relational world full of differential access to resources and asymmetric agential capacities, may in fact be the most primitive or "natural" disposition of any society or ecology, and perhaps the intuition of these early Christians (and maybe Marx) wasn't too far off. Or as Shontel Brown noted (see below), it may be at least partially up to us to make good on the promise of hospitality, enfolded as it is within "so simple a beginning," to quote Darwin's On the Origin of Species.

|

| Wayne Getz's consumer categories |

"A thing without oppositions ipso facto does not exist... existence lies in opposition." — CS Peirce

"Increscunt animi, virescit volnere virtus. (The spirit grows, [and] strength is restored, by wounding.) — Nietzsche

The heart’s wave would never have risen up so beautifully in its cloud of spray, and become spirit, were it not for the grim old cliff of destiny standing in its way." — Hölderlin

To quickly recap where we have been, the evolutionary origin of brain lateralization has often been explained by McGilchrist to be a consequence of predator and prey dynamics, where half of our neuroanatomy seeks out food while the other half is on the lookout so as not to become food. This was recently laid out again in a conversation with Eric Metaxas. But if we take a further step back, this may be about the “means-ends” distinction. In the instance of solving the conundrum of “how to eat” we may really be talking about a means. And in the case of “staying alive” we may really be talking about ends, because avoiding death raises existential questions about life. I'd suggest that these could be thought of as manifesting in the polarities of “carnal desire" and "filial piety,” or more abstractly, eros and agape. In the jargon of popular evolutionary terminology, we can also point to examples such as "sexual selection" and "parental care," if understood in a broad sense. These dynamics are extremely important for the continuation of a species, but each involves different cognitive processes with corresponding strengths and weaknesses. Complimentary, but also pulling in separate directions. It may seem almost cliché to say so, but in our contemporary culture, shallow carnal desires (attention hazards) are overshadowing deep filial care (helper therapy principle), in so many words, which could help explain "how we got stuck" in a LH captured, devitalized society of deceptive semiosis. That's also the motivating question of Graeber and Wengrow's book The Dawn of Everything. Today we tell people what to attend to, and let others tell us what to attend to, but we could ask how we can help others, and ask others for help. And all this can be handily united under the metatheoretical framework of the hemisphere hypothesis.

A Psychomachia of Binary Oppositions:

Left & Right (neurobiological)

Means & Ends (abstract philosophical)

Māra & Bodhisattva (religious and mythic)

Possess/Control & Care/Compassion (agentic virtues)

Eros/Carnal & Agape/Filial (psychological virtues)

Pathogenesis & Salutogenesis (disease and health)

Sexual Selection & Parental Care (evolved behavior traits)

Attention Hazard & Helper Theory (attentional dispositions)

Parasitic/Deceptive/Coercive & Mutualistic/Translucent/Permissive (semioethics of symbiosis)

Bayo Akomolafe recently wrote "When I speak of 'cracks', I am indeed speaking about the 'monster', an irruption of the paraontological, of the minor, into a weird disarchitecture of the normal - a rearrangement that releases us from the choreography of the fully anticipated... And we will emerge with glimpses of new forms of care as the world-we-know shudders to a composting end." To help flesh out this metaphor he turned to the Alien movie franchise, which has been very successful, in part due to its ability to tap into some very deep through-lines in culture. "Xenomorph" comes from the Greek xeno-, which translates as either "other" or "strange", and -morph, which denotes shape. The films are an exploration of our relationship with the alien "other," and in the starkest terms possible: the parasite and the host. Xenophobia writ large.

Akomolafe has an opportunity here to problematize our stable notions of who is the parasite and who is the host in this relationship: Who is really parasitizing whom? The actor Bolaji Badejo was dressed up as the archetypal parasite, which one might say is a curious inversion of the historical reality - it was the melanated bodies and indigenous cultures that were parasitized and exploited by European colonialism. In an attempt to rectify this inversion, Timothy Morton famously wrote "We are the Asteroid," adding another metaphor to the list. Others have before and since compared the modern West's exploitative mode of relating to that of a spreading cancer. But the metaphor of the parasitic organism is perhaps most fertile. And I say this for good reason. Lynn Margulis theorized that an endosymbiotic relationship initially begins as a parasitic relationship (one in which the "guest" lives at the expense of the host). However these zero sum relationships are metastable. They can evolve into a mutualism when the interests of both parties are brought into alignment, and this is most dramatically seen in the "philoxenic" case of endosymbiosis, where two bodies quite literally fuse into one. At this point, our metaphors begin to break down. But through their exploration I think the possibilities for transformation and, pathways toward "new forms of care," do suggest themselves.

Akomolafe often writes about the creation of sanctuary, a space between perfection and imperfection, where there is no compulsion to heal, include, empower, or celebrate. There are similarities with Japan's wabi-sabi, Thich Nhat Hanh's apranihita, Henri Nouwen's description of hospitality, and Taoism's wu wei. The myth of Hun-tun, perhaps most clearly, illustrates the consequences when we do not accept others as they are and trust them to follow their own developmental path:

The emperor of the South Sea was called Shu [Brief], the emperor of the North Sea was called Hu [Sudden], and the emperor of the central region was called Hun-tun [Chaos]. Shu and Hu from time to time came together for a meeting in the territory of Hun-tun, and Hun-tun treated them very generously. Shu and Hu discussed how they could repay his kindness. "All men," they said, "have seven openings so they can see, hear, eat, and breathe. But Hun-tun alone doesn't have any. Let's trying boring him some!" Every day they bored another hole, and on the seventh day Hun-tun died.

Jonathan Rowson wrote about how we need a new metaphysics and metaethics, and a new metapolitics to emerge from them. Philoxenia is somewhat unique as a value since it is paradoxically self-negating in the sense that it 'denies the self' to 'make room for the other.' That is, it provides 'right hemisphere' negative feedback, preventing any single value/ethic from claiming absolute primacy over all others. Thus hospitality, the only value that could, is constitutionally prevented from doing so, due to its very nature. And so it captures a lot of what many separate voices, which may bear superficial differences, are all working toward in diverse ways. It is a metanarrative, but also a metaphysical skeleton key that is able to open a pathway into conversations about axiology and values (metaethics), even for those who may otherwise be hesitant to begin such conversations owing to a deep (and often justifiable) skepticism of where they might lead. Such discussions may be necessary for grounding a new metapolitics capable of generating meaningful change. (Furthermore, the self-negating aspect that makes room for the other, is necessary to hear the children. Mt. 19:14)

|

| Xenia as portrayed by Rubens (1630–33) |

“I was most afraid, but even so, honoured still more that he should seek my hospitality.” - Snake, by D.H. Lawrence

“To call myself beloved, to feel myself beloved on the earth.” - Late Fragment, Raymond Carver

“It is not good that the human should be alone; I will make them an help meet for them... and the two shall be one flesh.” - Genesis 2:18-24

As a social lens, hospitality reveals both the large-scale organization of welcoming (and excluding) others at the institutional or state level and the everyday experiences of living with difference. At the same time that discourses of hospitality reproduce conventional performances of togetherness, however, they also open up the possibility of doing togetherness differently – of imagining inside and outside, stranger and friend, self and other, host and guest in new, radical and potentially dangerous ways. Among the research areas that we feel merit further attention and debate are: embodied hospitality, historical approaches to hospitality, and narrative hospitality [cf. 'narrative therapy']. The examination of narrative hospitality through, for example, literature, autobiography and travel writing is a rich and under-developed seam that can enhance our understanding of hospitality. Likewise, the study of depictions of hospitality through moving and still images and representations has much to contribute. And historical analyses bring the incredibly rich and contested legacy of hospitality to bear on contemporary practices. Studies ranging from ancient customs and religious traditions to postcolonial articulations of hospitality help to make sense of the philosophical, political and ethical dimensions of social relations in a globalized world." [Regarding embodied hospitality, it may be that many diseases of affluence are also diseases of disembodiment. Those living in Western cultures may have simply become too disembodied, as the guest increasingly ignores the host.]

"There’s a dilemma which Derrida asserts to be an inescapable feature of the concept Of Hospitality, which we see vividly revived in each successive refugee crisis, and in every discussion about immigration. If refugees fleeing from persecutors find their way through an opening, it cannot be equally open to those pursuing them. Both sides of the dilemma must always be kept in mind, and the idealistic claims of an unrestrained hospitality, though impossible to follow as a law, must never be completely silenced by claims of impracticality. In his later writings Derrida repeatedly uncovers similar dilemmas inherent in the central terms of our contemporary political thinking. He does this not to dismiss these concepts, but to show the doubled attention that each requires of us. Failures in these fields occur when one side of the dilemma temporarily obliterates our awareness of the other. The hospitable person or country should be seeking at all times to be more hospitable, alert to any opportunities to move in this direction, never saying “we’ve done enough, we can’t do more,” rather, always seeking practical ways to do more than we have.”

“Instead of making apocalypse movies to help us dehumanize the masses at the gates, we can create stories that help people remember that the sign of an advanced civilization is how well they treat the stranger. This was God's test of Lot in the Bible, and it's the reason he and his family were spared the destruction of Sodom. They welcomed and protected the stranger. And that's how to survive in the apocalypse, because an apocalypse really just means revelation or unveiling, not an ending. Instead of thinking tit for tat, or running away, or strategizing for the end, we refuse to see the world as ending. Instead of buying into their nightmare, and accepting their limited vision of how things can be, embrace the stranger, share your food with them, and together build the reality we all know is possible, even probable. Do the opposite of what they do. Meet their hate with love. Counter their selfishness by sharing. Instead of building walls to keep out the others, open doorways that welcome them home. We can do this. So no more doom and gloom. That's their game.” [Rushkoff: "For me right now, mattering is being as hospitable as I can to everybody. It's hard enough (maybe because I'm mean deep down)."]

The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas (1973) can be read as a rejoinder to stories like The Cold Equations (1954). Both are short stories that use a kind of reductio ad absurdum, pushing an argument to the limits of logic to show where it breaks. The city of Omelas is a perfect utopia, except for one child who is held prisoner to suffer for all. Most in Omelas accept this bargain, but the ones who walk away from Omelas exemplify a higher morality, rejecting injustice and accepting the unknown, perhaps even death, instead. In her introduction to her debut novel The Left Hand of Darkness, written some years after its publication, Le Guin devastates the Cambellian idea of speculative sci-fi stating that it always arrives somewhere between the gradual extinction of human liberty and the total extinction of human life. If The Cold Equations argues that reality is a machine that does not care, Omelas replies, even so, the only moral path is to resist, whatever the consequences.In her essay “Myth and archetype in science fiction,” Le Guin talks about the place of Jungian symbolism in her storytelling. It’s clear that the Earthsea novels are expressions of Carl Jung's theory of archetypes. And The Lathe of Heaven is a metaphor for the human will to power. Le Guin believed that the mind and imagination can shape reality. Those with real power have always known this. There is the constant threat that those who win the fight for reality are those with the strongest will, but the least wisdom. Caesars and kings, politicians and popes, billionaires and media magnates all know that part of their power rests on controlling the narrative, shaping the ideas and concepts that in turn shape our reality. The power of Ursula Le Guin's storytelling is that it reaches into our dreams and imaginations, it weaves meaning from symbol, metaphor, and archetype. It crafts mythic stories to awaken all who read it to the deep truths of reality. [Similarly, HG Wells stated that "Literature like architecture is a means, it has a use." ...All of which is just to say that the host-guest archetype could use a storyteller like Le Guin to bring it to elevate it into our collective consciousness...]

"Omotenashi is a portmanteau. “Omote” meaning public face — an image you wish to present to outsiders. “Nashi,” meaning nothing combined, suggests that every service comes from a place of transparency and the bottom of the heart — honest, no hiding, no pretending... The level of hospitality and service received in Japan is unquestionably the best in the world... A hospitality setting can be meticulously designed as a holistic experience... What’s groundbreaking about omotenashi is not its novelty but its ability to reveal something fundamental that has, for decades, been overlooked in the hospitality industry—the soul of hosting. It’s a call to strip away the performative layers of hospitality to expose its core, which is a shared humanity. It turns every interaction into an exercise in empathy, making both the host and the guest co-authors of an unfolding story."

In traditional Japanese aesthetics, fukinsei (不均整), is asymmetry, which is related to wabi-sabi (侘び寂び) which in turn is often described as the appreciation of beauty that is "imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete" and is prevalent in many forms of Japanese art. But at the same time, this aesthetic could be positively described as that which reveals the evidence of (the survivorship bias of) hospitality, of having been used and (presumably) appreciated by another. Central to wabi-sari is the concept of omotenashi, which, as noted above, revolves around hospitality, and which is abundantly in evidence during sadō/chadō (茶道) which literally means 'The Way of Tea' but is more popularly recognized as tea ceremony. The wabi-sabi aesthetic is cross cultural, as we can see in Eric Sloane's books and drawings of the vernacular architecture of early pastoral America, and the nostalgia for a more hospitable past. One may even wonder: How many social movements are motivated by the simple felt loss of public hospitality? This feeling seeps in everywhere and prompts some reflection. (Why is roadkill the acceptable collateral damage of our desire for omnipresence? Would a little door built above windows, allowing bees trapped behind the glass to escape, or fine mesh to prevent birds from colliding with windows on the opposite side, be too difficult for us to accommodate?)

[Love is often categorized into four types by contemporary philosophers: love as a union, robust concern, valuing, and emotion. Ancient Greek philosophers identified six forms of love: familial love (storge), friendship or platonic love (philia), sexual or romantic love (eros), self-love (philautia), guest love (xenia), and self-emptying or divine love (agape). In Japan, the concept amae (Japanese: 甘え), describes the dependency and emotional bonds between an infant and its mother — a bond that lays the foundation for the archetypal concept of love.

In Confucian philosophy, the concept of ren (Chinese: 仁) emphasizes the cultivation of harmonious relationships within society, starting from the family unit and extending outward. These relationships are delineated by five main categories: father-son, older brother-younger brother, husband-wife, older friend-younger friend, and lord-servant. They bridge the gap between the human and the divine. The Chinese philosopher Mozi developed the concept of ai (愛) to replace what he considered to be the long-entrenched Chinese over-attachment to family and clan structures with the concept of "universal love" (jiān'ài, 兼愛). In this, he argued directly against Confucians who believed that it was natural and correct for people to care about different people in different degrees, which betrays a very utilitarian perspective.

In Taoism, the concept of ci (慈) embodies compassion or love, with connotations of tender nurturing akin to a mother's care (cf. amae). This emphasizes the idea that creatures can only thrive through raising and nurturing. It transcends preconceived notions of individuals, seeking connections that surpass distinctions and superficial reflections. Taoist responses to the loss of a loved one as portrayed in the Zhuangzi may involve either mourning their death or embracing the loss and finding joy in new creations (cf. Kisa Gotami).

The "host-guest archetype" refers to the archetypal dynamic between a host, who welcomes and accommodates, and a guest, who is received and enters the host's space. The welcoming tavern keeper or inn owner is a popular example. In Homer's Iliad, the Trojan warrior Glaucus and the Greek hero Diomedes discover their grandfathers were guest-friends. Instead of fighting, they honor the ancient bond by exchanging armor, illustrating how the code of hospitality can transcend enmity. In Japanese folklore Zashiki Warashi are household spirits resembling children who bring good fortune and prosperity to the homes they inhabit (not an onryō like Sadako in The Ring). A family that respects and is kind to their zashiki warashi will thrive. However, if the spirit feels disrespected, it will leave, and the family will face decline and ruin.]

In An Introduction to Comparative Philosophy, my former Eastern philosophy teacher Walter Benesch noted that "some Chinese philosophers [Xunzi] refer to the mind as empty. They compare it to a rice bowl whose usefulness and function, even when it is full of rice, is its emptiness." I would note that ceramic art, as that of 橋本昌彦 (Hashimoto Masahiko) is often displayed with flower arrangements, though could equally be displayed with the matcha (抹茶) used in sadō, or of course food (whether in storage or prepared for a meal). And in his class lectures, Benesch noted that traditional Chinese landscape paintings often included human figures or structures somewhere within the scene. In part, this reflects the Daoist and Confucian belief that nature isn't complete without humans. We are not only connected to our environment, we are an inseparable part of nature. This is an expression of hospitality. It is also interesting to observe that this pattern has repeated itself with the advent of the futuristic art of science fiction. Here we see images of exotic alien worlds, but frequently not without humans (or human-like figures) and their habitations somewhere within the scene, someone or some thing familiar that we can empathize with. Whether these new images represent delusional aspirations or not, our hope to find a hospitable new home, wherever we find ourselves, continues. ...Today I observed that when a dog meets another dog on the neutral ground of a public park, their greeting is often amicable. But when a dog meets another on the other's home territory, the intrusion is not always well received. There may be limits to hospitality when we travel abroad.

How does hospitality manifest within culture? The notion of a "guest of honor" is widely recognized. "Hostels" provide low cost shelter for itinerant travelers. A "hospice" is a home giving palliative care to the sick or terminally ill, also derived from the same Latin root hospes. This has been lately also applied to a notion of "hospicing modernity," or the sick culture of our present age by any name (perhaps "hospicing postmodernity"). In a religious context, taking "refuge" refers to the protection and guidance, indeed the hospitality, that the devotional way of life provides the religious adherent. And Dorothy Day and Charles Mully are two examples of people who have, in their own ways, attempted to apply and extend the concept of hospitality for real, practical effect, thereby making the world itself a more hospitable place.

There seems to be a move away from inherently divisive "identity politics," which invokes the frame of good and bad identities, friends and foes, and instead move toward something much more like a "values based politics" so we can have conversations about the shared values (like hospitality) that are important to all of us, regardless of whatever our personal identity may be. One of the roles of the federal government is to embody the ethos of "E pluribus unum" and thus offer ways for how we might rise above a politics of resentment. Instead of intransigently digging in our heels, we can reframe the discussion. Paraphrasing something Albert Einstein may have once said, “You cannot solve a problem with the same mind that created it.” We need to be talking about those values that bind our families, communities, and our nation together ("participation in the evolution of value" per Zak Stein, which should call to mind "McGilchrist's Wager"). As Sarah McBride said: "I think that a politics that is rooted in opposition to an enemy is fundamentally regressive. We can put forward an aspirational politics that isn’t defined by who we are against, but by what we are for and about who we can be. And I think that is a more successful path for progressive politics than an enemies based politics, which so often devolves to anger. You can have effective politics, and good politics, and better outcomes, with an aspirational politics, with a politics that isn’t just about what it’s opposed to, but about what it can build and who we can be."