Yesterday I finished reading “Signs of Meaning in the Universe” by Jesper Hoffmeyer, which appeared as "En Snegl På Vejen: Betydningens naturhistorie" (A Snail on the Trail: The Natural History of Signification) in the original Danish, and I’ll be thinking about it for a long time. He’s as sweeping as David Grinspoon and Peter Corning in breadth, but in addressing subjective meaning he’s more intimate than either. It’s one of those books that can change the way you see everything. Hoffmeyer wrote “Back in the seventies when, as a young biochemist, I first realized how serious the problems of pollution and global ecology were I began for the first time to suspect that a serious imbalance existed between living things and the science of living things, that is to say biology. ...The determination of humanity’s place in the natural scheme of things was far from being in safe hands.“ (90) This imbalance was also noticed by Rosi Braidotti, when she remarked that the conventional Humanities suffer from a lack of adequate concepts to position subjectivity in a continuum with the totality of things.2"The biosphere must be viewed in the light of the semiosphere rather than the other way around."

- Jesper Hoffmeyer

All living organisms are guided by natural and artificial signs that (1) enable organisms to flexibly adapt their activities to constantly changing conditions, (2) structure and organise individual behaviour within the larger community, and (3) serve as a means of coordination and communication among and between diverse species, where nothing exists in complete separation from anything else.

- Paulo De Jesus

After ecology has delineated the relationships between different agencies (individual species, populations, communities, and ecosystems), biosemiotics integrates these matter/energy dynamics with information, communication and meaning. The result is a combined empirical and epistemological exploration of ecological complexity that is able to provide a more detailed description of the interactions between organisms, their aggregation, and resources.

- Almo Farina

“We must look at adaptation as a semiotic phenomenon, that is, as a process of signification.” - Eugen Baer

"The logic of evolution produces a tendency to greater extents of 'semiotic freedom' or semiotic abstraction and complexity." - Wendy Wheeler

"Signs are triadic relations: one thing representing another than itself to yet another." - John Deely

"Truth may be found in signs whatever their kind." - Aristotle

Some approaches to semiotics see it as basically the study of words or other signs that refer to some object in the world. Signifier, signified. The relationship of one thing to another thing. But C. S. Peirce's major insight was that signs don't do anything on their own. There's only meaning because someone sees meaning in it. In other words, the reaction is the thing. In technical terminology, this third piece is called the "interpretant."3 “Semiotics is the study of meaning-making – the process of how people interpret and make sense of life events, relationships, and the self. Biosemiotics is the combination of the scientific fields of semiotics and biology and studies the prelinguistic meaning-making, or production and interpretation of signs and codes in the biological realm.”4 Hoffmeyer expands further by introducing the semiosphere. "The concept of the semiosphere adds a semiotic dimension to the more well known concept of the biosphere, emphasizing the need to see life as belonging to a shared universe of sign activity through which cells, organisms and species all over the planet interact in ways that we still hardly understand." But why a "sphere?" How do these signs integrate/interact? "In semiotic interactions behavioral or morphological regularities (habits) developed by one species (or individual, tissue, or cell) are used (interpreted) as signs by individuals of the same or another species, thereby eliciting new habits in this species, eventually to become sooner or later, signs for other individuals, and so on in a branching and unending web integrating the ecosystems of the planet into a global semiosphere."5 If this is a fair representation, then it is clear that if we do not "recognize the signs" present in our environment, the indicators of harm, or opportunities for healing, then we become more vulnerable, with grave implications for future survivability. In other words, if you can’t see the smoke, you might burn in the fire.

“At the ecological level biosemiotics requires us to extend our concept of an ecological niche to embrace the semiotic niche, i.e., the totality of cues around the organism (or species) which the organism (or species) must necessarily be capable of interpreting wisely in order to survive and reproduce. ...This implies that the relative fitness of changed morphological or behavioral traits become dependent on the whole system of existing semiotic relations that the species finds itself a part of and, accordingly, the firm organism-versus-environment borderline will be dissolved, and a new integrative level intermediate between the species and the ecosystem would have to be considered—i.e., the level of the ecosemiotic interaction structure.”6

I believe that Jesper Hoffmeyer's "semiosphere" is similar to Foucault's "governmentality.” For if one has control over the signs in the milieu, one has the surest route to gain influence over the relationship between the "interpretants" and the "objects," which is to say, the people and their environment. C. S. Peirce said that "all this universe is perfused with signs, if it is not composed exclusively of signs” Given this perspective, humans are just one type of semiotic process, rather than the sole controller, interpreter and generator of signs (the anthropocentric view). The fascinating thing is that once we leave anthropocentrism behind, regardless of how that is done, the tools and methods of governance shift in likewise manner. Given the framework of indirect realism, if you know the representational theory of mind, that is to say, the process of biosemiosis, then instead of directly engaging with subjects, governance can be effectively achieved by indirect engagement with the environment as a whole as opposed to direct engagement with subjects. The "action without action" of the Tao Te Ching, as it were.

|

| A Biosemiotic Approach |

I’ve encountered the field of semiotics before (and not just through stigmergy). Maynard Smith links the study of animal signals to the field of semiotics, the communication of meaning, and of which Umberto Eco wrote, tongue in cheek, "semiotics is in principle the discipline studying everything that can be used in order to lie." Eco further proposed that every cultural phenomenon can be studied as communication. In 1984, Richard Dawkins, perhaps the most famous ethologist alive, characterized animal signaling as an arms race between signalers as 'manipulators' and receivers as 'mind-readers.’ In 2010 Dawkins introduced me to Amotz Zahavi, through a casual reference made in “The God Delusion.” Zahavi developed his version of “signaling theory” in his book “The Handicap Principle: a missing piece of Darwin's puzzle” and redefined Darwin's original categories of natural selection and sexual selection as utilitarian selection and signal selection, respectively. More recently, having read "Synergistic Selection" (Peter Corning), "The Secret of Our Success" (Joseph Henrich), and "Earth in Human Hands" (David Grinspoon), I see "Signs of Meaning in the Universe" by Jesper Hoffmeyer as a work that is clearly of the same caliber. He draws together Pierce, Uexküll, and Darwin into a single vision. If the implications for future research weren't enough, the historical context it provides definitely is.

Keywords: semiotics, semiosphere, semioethics, ecosemiotics, cognisphere, biosemiosphere, semiome, semiosis, realism, indirect realism, mental representation, pragmatism (fallibilism), metasemiosis, subjectivity, suprasubjectivity, information (data), epistemology (knowledge), connection, relationship, relational ontology, meaning (definition, denotation, interpretation), sign (signification, significant, significance)

Natural examples: hares and foxes; parasitic wasps, caterpillars, and plants; honeyguide birds; Clever Hans (horse); birds that feign injury; wolves and sheep, land mine sniffing rats, dogs and illegal drugs.

Postscripts (Partial Outline):

Terminology and historical context

Terrence Deacon on causality and normative consequences

John Flach and cognitive systems engineering

Winfried Nöth on machine semiosis and computer science

Almo Farina and a "General Theory of Resources"

Peter Harries-Jones and communicative order

Paulo de Jesus and biosemiotic enactivism

Susan Petrilli and semioethics, semiocide, and symptomatology

John Deely on suprasubjectivity

Wendy Wheeler on semiotic freedom

Biosemiotics, genetics, and evolutionary transitions

Biosemiotics in the Case of Global Climate Change

Biosemiotics and Climate Action Plans

Cultural implications of biosemiotics

Semioethics and activism in Alaska

Social Science emphasis only:

pedagogy and edusemiotics

semioethics, semiotic freedom and constraints

social semiotics and social credit systems

fallibilism, misinformation, and deception

ecosemiotic health and disruption

1. Terminology and position within academia

For a bit of history of terms, semiotics derives from the Greek σημειωτικός "observant of signs." By comparison, cybernetics derives from the Greek κυβερνήτης "steersman, governor, pilot, or rudder." There’s a relation between these: in order to steer a ship and clear the shoals and eddies, one must be able to read the weather and the waves. Semiotics, as a field of study, is situated within the 'philosophy of information', and as a result has direct implications for both biology and the philosophy of mind.

1.1 Historical context

More often than not, academic papers tend to be very dry to read. But from time to time there are those writers who are both experts and skilled storytellers, pulling you into the mysteries they uncover. John Deely was one of these people. In his paper he begins by tracing the early beginnings of semiotics with Hippocrates (370 BC) who used the notion to establish medicine as a scientifically founded art, through Plato (385 BC), Aristotle (347 BC), the Stoics and Epicureans (300 BC) who debated the difference between natural and conventional signs, Origen of Alexandria (253 AD), Augustine of Hippo (430 AD), Thomas Aquinas (1274), Duns Scotus (1308), John Poinsot (1632), John Locke (1690), Charles Peirce (1867), Jakob von Uexküll (1940), all the way up to the diversity we see today with Bateson, Sebeok, Hoffmeyer, and Deely himself. Origen's place in this timeline was suggested by Wendy Wheeler, all others by Deely. There are certainly many others that could be added, and the field today is probably more diverse than at any time in the past. This is a very brief timeline only intended to add

historical context.

Semiotic consciousness endured in Western Europe until the first modern philosophers switched the attention from suprasubjectivity to the being of the mind. Peirce effectively picked up again where Poinsot left off. As Deely writes "Peirce was able to recover the Latin notion of 'signum' very nearly at the point where the Latins had left it, that is to say, at the point where it had been realized and definitively explained that signs strictly speaking are not their sensible or psychological vehicle, but that this vehicle is not subjective but suprasubjective..." This is a critical point. Like signs themselves, meaning/significance is always one step removed from the thing/process. "If the most important development for the immediate future of philosophy (and perhaps for intellectual culture as a whole) is to be, as I believe, the realization of the centrality of the doctrine of signs to the understanding of being and experience for human animals, then Peirce’s recovery of the notion of signum from the Latins may be said to have marked the beginning of a new age in philosophy." And elsewhere: "Sebeok made the point that semiotics provides the only transdisciplinary or “interdisciplinary” standpoint that is inherently so; in other words, semiotics thematizes the study of what every other discipline had (perforce) taken for granted - semiosis... What is distinctive of the action of signs is the shaping of the past on the basis of future events; the future beckons the present to draw upon the resources it has from the past... theoretical justification and practical exploration of this hypothesis marks the final frontier of semiotic inquiry."

Deely, John, The role of Thomas Aquinas in the development of semiotic consciousness (2004)

Deely, John, The Impact of Semiotics on Philosophy (2000)

1.2 Semiotics: the study of the possibility of being mistaken

In his glossary at the end of "Peirce: A Life", Joseph Brent includes this definition:

"Fallibilism. The doctrine, a consequence of pragmatism, that no matter how completely we may believe that some claim we make about reality is true, it remains radically subject to error. Even though certainty is impossible, because of the continuity of mind and matter, we can be secure in our everyday knowledge of the world and are justified in believing that we can correct errors."

In his book "Four Ages of Understanding" Deely writes "Semiotics as the study of the possibility of being mistaken. Peirce had another name for pragmaticism. He also called this way of thinking fallibilism; and insofar as pragmaticism is conceived in function of the doctrine of signs, this alternative designation for it is truly excellent. For just as the sign is that which every object presupposes, so the study of signs and the action of signs, semiotics, is eo ipso the study of the possibility of being mistaken. The movement of human understanding from confusion in its first apprehension to clarity, unfortunately, is not a simple linear development from confusion to the clear grasp of truths. It is just as often a development from confusion to a clarity that is mistaken."

This reminds me of what Jacob Bronowski eloquently stated years ago: "We are always at the brink of the known; we always feel forward for what is to be hoped. Every judgment in science stands on the edge of error and is personal. Science is a tribute to what we can know although we are fallible. In the end, the words were said by Oliver Cromwell: 'I beseech you in the bowels of Christ: Think it possible you may be mistaken.'"

Brent, Joseph, "Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life" (p352)

Deely, John, "Four Ages of Understanding" (p636)

Bronowski, Jacob, "The Ascent of Man" (p374)

1.3 Physiosemiosis

"The search for the non-biological regularities of the universe that alone make semiosis veridical becomes a field of (at least theoretical) investigation in its own right. Deely designates this field – which examines the pre-existing “patterns of knowability” or “virtual thirdness” inherent in the regularities of the non-living surround that can potentially function as signs for some agent – as physiosemiotics, to distinguish it from what he considers as the “dangerously misguided” notion of pansemiotics, which would designate the polar opposite belief that the semiosis of living being is inherent in all non-living things.

Deely, John, "Physiosemiosis and phytosemiotics" (1990), as quoted by Donald Favareau in "Essential Readings in Biosemiotics" (2010)

Semiotic consciousness endured in Western Europe until the first modern philosophers switched the attention from suprasubjectivity to the being of the mind. Peirce effectively picked up again where Poinsot left off. As Deely writes "Peirce was able to recover the Latin notion of 'signum' very nearly at the point where the Latins had left it, that is to say, at the point where it had been realized and definitively explained that signs strictly speaking are not their sensible or psychological vehicle, but that this vehicle is not subjective but suprasubjective..." This is a critical point. Like signs themselves, meaning/significance is always one step removed from the thing/process. "If the most important development for the immediate future of philosophy (and perhaps for intellectual culture as a whole) is to be, as I believe, the realization of the centrality of the doctrine of signs to the understanding of being and experience for human animals, then Peirce’s recovery of the notion of signum from the Latins may be said to have marked the beginning of a new age in philosophy." And elsewhere: "Sebeok made the point that semiotics provides the only transdisciplinary or “interdisciplinary” standpoint that is inherently so; in other words, semiotics thematizes the study of what every other discipline had (perforce) taken for granted - semiosis... What is distinctive of the action of signs is the shaping of the past on the basis of future events; the future beckons the present to draw upon the resources it has from the past... theoretical justification and practical exploration of this hypothesis marks the final frontier of semiotic inquiry."

Deely, John, The role of Thomas Aquinas in the development of semiotic consciousness (2004)

Deely, John, The Impact of Semiotics on Philosophy (2000)

1.2 Semiotics: the study of the possibility of being mistaken

In his glossary at the end of "Peirce: A Life", Joseph Brent includes this definition:

"Fallibilism. The doctrine, a consequence of pragmatism, that no matter how completely we may believe that some claim we make about reality is true, it remains radically subject to error. Even though certainty is impossible, because of the continuity of mind and matter, we can be secure in our everyday knowledge of the world and are justified in believing that we can correct errors."

In his book "Four Ages of Understanding" Deely writes "Semiotics as the study of the possibility of being mistaken. Peirce had another name for pragmaticism. He also called this way of thinking fallibilism; and insofar as pragmaticism is conceived in function of the doctrine of signs, this alternative designation for it is truly excellent. For just as the sign is that which every object presupposes, so the study of signs and the action of signs, semiotics, is eo ipso the study of the possibility of being mistaken. The movement of human understanding from confusion in its first apprehension to clarity, unfortunately, is not a simple linear development from confusion to the clear grasp of truths. It is just as often a development from confusion to a clarity that is mistaken."

This reminds me of what Jacob Bronowski eloquently stated years ago: "We are always at the brink of the known; we always feel forward for what is to be hoped. Every judgment in science stands on the edge of error and is personal. Science is a tribute to what we can know although we are fallible. In the end, the words were said by Oliver Cromwell: 'I beseech you in the bowels of Christ: Think it possible you may be mistaken.'"

Brent, Joseph, "Charles Sanders Peirce: A Life" (p352)

Deely, John, "Four Ages of Understanding" (p636)

Bronowski, Jacob, "The Ascent of Man" (p374)

1.3 Physiosemiosis

"The search for the non-biological regularities of the universe that alone make semiosis veridical becomes a field of (at least theoretical) investigation in its own right. Deely designates this field – which examines the pre-existing “patterns of knowability” or “virtual thirdness” inherent in the regularities of the non-living surround that can potentially function as signs for some agent – as physiosemiotics, to distinguish it from what he considers as the “dangerously misguided” notion of pansemiotics, which would designate the polar opposite belief that the semiosis of living being is inherent in all non-living things.

Deely, John, "Physiosemiosis and phytosemiotics" (1990), as quoted by Donald Favareau in "Essential Readings in Biosemiotics" (2010)

2. A sphere of infinite semiosis

2. A sphere of infinite semiosis"The concept of semiosphere was first formulated by Juri Lotman in 1982. He compared it with biosphere, the concept as described by Vladimir Vernadsky. In concordance with Sebeok’s thesis on coextensiveness of life and semiosis, Jesper Hoffmeyer has introduced the concept of semiosphere as covering semiosis of all life processes. According to Vernadsky, biosphere is the matter that is chemically changed in result of life processes (whereas noosphere is the matter that is chemically changed in result of human mind). Semiosphere is not the matter but the whole set of semiotic relations. We describe the main elements of the model of semiosphere, as introduced by Lotman. Theory of semiosphere can be seen as a basis for general semiotics."

Kotov, Kaie; Kull, Kalevi 2011. Semiosphere is the relational biosphere. In: Emmeche, Claus; Kull, Kalevi (eds.), Towards a Semiotic Biology: Life is the Action of Signs. London: Imperial College Press, 179–194.

Meanings and values learned and discovered in our sign systems are not “located” “in” anyone’s head or any-where, but are cognitive-social events that we activate and instantiate by using our “cognitive-symbolic resources. Umberto Eco uses the phrase ‘unlimited semiosis’ to refer to the way in which meaning is a process. In Peirce's triadic model of semiosis the "action" of a sign is a limitless process of infinite semiosis, where one "interpretant" (or idea linked to a sign) generates another. In his book "The Play of Musement" (p11), Thomas Sebeok pointed out that Heraclitus supplied the essential link between the biosphere and the semiosphere, in his aphorism: "I went in search of myself". Sebeok went on: “there is a structural isomorphism between the inner personal world of the psyche and the vaster natural order of the universe... What Heraclitus meant was that once he encountered the law of the microcosmos within himself, he discovered it anew in the external world."

Logos Group, Peirce, Eco, and unlimited semiosis (2014)

Irvine, Martin, From the Film Arrival to Semiotics (2017)

3. Applications: symbiotic relationships

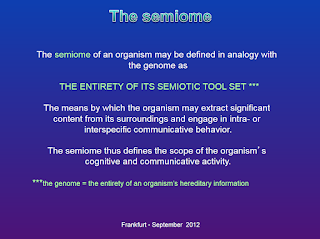

There are many topics that biosemiotics may shed light on. One is in regard to Dawkins' theory of the extended phenotype, which dissolves the supposed unity between the organism and its genome. How, it must be asked, can the receiver (in some instances this is the host) be got to behave according to the interests of the sender (or parasite, in parasitism)? [See reference to indirect realism above.] Less pernicious mutualistic relationships present similar challenges for explanation. This may be where the concept of the "semiome" becomes useful.

3.1 Applications: sensory specific satiety, fiber, emulsifiers, and the microbiota

Studies show that the greater the variety of food choices in front of us, the longer it takes to feel full, a phenomenon known as sensory specific satiety. “It’s the reason you always have room for dessert at a restaurant even when you’re full,” Dr. Pontzer said. “Even though you’ve had a savory meal and you can’t eat one more bite of steak, you’re still interested in the cheesecake because it’s sweet and that button hasn’t been worn out in your brain yet.” The Quantified Self movement, with it's data-driven insights into human behavior patterns, can shed light on these and similar biological predispositions to help us make more informed decisions. But note, a purely "quantified" self is devoid of significance, and so that meaning must be supplied by whomever utilizes the data. Perhaps a better label for the movement would be "semiotic self".

“Antagonizing the microbiota by highly processed diets — starving it by removing fiber and attacking it [with emulsifiers] — promotes inflammation.” That can hamper the body’s ability to feel satiated and result in overeating. For example, eating causes the body to release the hormone leptin, which quells hunger. But inflammation interferes with leptin’s action. “Put another way, our results do not question the notion that the obesity epidemic is driven by overeating,” he added. “Rather, it suggests that such overeating is driven, in part, by alterations in the microbiome inducing inflammation.”

Belluz, Julia, Processed foods are a much bigger health problem than we thought (2019)

3.2 Applications: Phytomining and phytosemiosis

Monica Gagliano performed research with plants, as she describes: "Just as Pavlov used a bell to condition a dog, if you present a fan to condition a plant, the plant will anticipate light following the stimulus. Eventually the plants learn that "just by the fan, I can start preparing and turn towards the light, because the fan tells me where the light is going to be". Somehow a decision is being made based on a value system. How much do you want that light? What does the fan mean? And just like for the dog, not all plants are the same. The plant is deciding and choosing based on how it feels about things, and the experience of those things. Just like for the dog, the plant is actually stretching the field of perception, because dinner, in this case the light, is actually not even there (at the moment the stimulus of the fan is presented). So you know where I’m going, just as with Pavlov's dog, the food is actually a concept, an idea in the plant’s mind. Or in other words, the plant is imagining the food arriving."

"The field of biosemiotics has contributed extensively to an inclusive conception of language that transcends its rigid alignment with verbal utterance. Particularly drawing on the work of American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, German biologist Jakob von Uexküll, and Danish biologist Jesper Hoffmeyer, contemporary biosemiotics generally conceives of language as an evolutionary response that humans share, albeit in different manifestations, with other forms of life. Following on Peirce’s footsteps, the biosemioticians of today have likewise argued that language is “pervasive in all life.”

Gagliano, Monica, Plant Intelligence and the Importance of Imagination In Science (2018)

Vieira, Patrícia, Monica Gagliano, and John Ryan, Introduction to The Language of Plants (2017)

In the context of the increasingly intertwined future that both humans and the planet have in the Anthropocene, the biosemiotic signalling processes in organic material can be used to contribute to the betterment of the planet. In this paper phytomining is described in the context of biosemiotics.

Gapševičius, Mindaugas, Semiotic Thresholds, Between Arts and Biological Science: Green Technology and the Concept of Phytomining (2018)

3.3 Applications: Social semiotics and socio-semiotic research (compare with Alex Pentland's "social physics")

Social semiotics includes the study of how people design and interpret meanings, how semiotic systems are shaped by social interests and ideologies, and how they are adapted as society changes. When considering notions of environmental justice, this subject has direct relevance. A social semiotics approach can be used to raise awareness of how each choice we make affects other choices, and can ultimately affect the wider social semiotic context of which we are part. We not only communicate already established social meanings and norms, but also assess those norms and, where necessary, create alternative meanings and norms. A socio-semiotic research project begins by making an inventory of multimodal semiotic resources and investigates how they are used in context to produce objects, form knowledge, and how they change over time. For example, if signs of climate change enter the public awareness and a shift to cleaner forms of energy and other industrial processes is sought, then identifying the current semiotic processes within society will allow us to see where social inertia and resistance to change may prevent the rapid uptake of these alternatives.

Social Semiotics in the Classroom (2018)

Social Semiotics (2011)

In a lecture he gave, Nicholas Christakis said that “our experience of the world depends on the actual structure of the networks in which we are residing, so I came to see these signs of social networks as living things that we could put under a kind of microscope and study and analyze and understand." This bears obvious similarities to Peter Corning’s study of synergy, Alex Pentland’s social physics, and perhaps Thomas Sebeok’s semiotic web. Could it be that a social network is a semiotic network by another name?

3.4 Social credit systems

Social credit systems haven’t just appeared from nowhere. Their long history is well documented in this article by Mara Hvistendahl on how Alipay is used in China. More recent advances in computational social science and related fields have pushed these capabilities still further. In addition, David Brin pointed out that India's version, Aadhaar, will also be very big, so we must be prepared to answer such surveillance with sousveillance. Daniel Estrada developed a proposal called Polytopolis, a self-organizing governance framework designed to work on stigmergic principles to allow for radically decentralized normative policies to develop. As he wrote in a separate article “We must have digital tools for generating spontaneous direct actions and broad democratic consensus as the political needs arise. These tools must operate openly, transparently, and independent of any centralized state or corporate control.” Heather Marsh likewise applied stigmergy to government, and biosemiotician Victoria Alexander noted that creative and intelligent behavior emerges when individuals have semiotic freedom. Semiotics, as applied to social credit systems, is sure to grow.

3.5 Applications: political manipulation and post truth polarization

"The illusion of choice is the most important of illusions, the main trick of the Western way of life in general and of Western democracy in particular, which has long been committed to the ideas of Barnum rather than Cleisthenes. ...Foreign politicians ascribe to Russia interference in elections and referendums across the globe. In fact, the matter is even more serious - Russia interferes in their brains, and they do not know what to do with their own altered consciousness. Since, after the failed 90s, our country abandoned ideological loans, began to produce meanings and switched to the information counteroffensive to the West, European and American experts began to err in their forecasts more and more often. They are surprised and enraged by the paranormal preferences of the electorate. Confused, they announced the invasion of populism. You can say so, if there are no words."

Surkov, Vladislav, Putin's Long State (02/02/2019)

In "The Road to Unfreedom", Timothy Snyder describes how Russian leaders first mastered “fake news” in the digital era as part of a broader strategy to disorient their own society. It went something like this: Use the internet and TV to flood society with misinformation, demonize the institutions charged with uncovering facts, and then exploit the confusion that results. By cultivating enough chaos, people become cynical about public life and truth itself. The intended message is that you can’t trust any information, you can’t trust anyone or anything. There’s no reason to believe in anything. There is no truth. Your institutions are bogus.

"In the 2010s, Russia began to deploy these techniques abroad as a means of destabilizing Western countries (an information counteroffensive, per Vladislav Surkov). In Trump, they found a particularly useful tool that they could use to stoke America’s internal divisions and subvert democracy. We’re now in a world in which information warfare is one of the primary modes of warfare and Russia, more than anyone else, is uniquely prepared for this kind of conflict. Americans often think that it’s not real war if it doesn’t involve combat, but that’s not how the Russians see it. War is about breaking the will of the enemy, and historically, combat was the means to that end. But you can break a country’s will without combat, and that’s how Russia uses misinformation."

Lawrence Martin-Bittman, who spread disinformation as a spy before teaching at Boston University remarked that at first, “it was too hard for Americans, especially journalists and scholars, to accept that deliberately false stories could be planted in our news media.” But it was only a matter of time before corrupt political groups everywhere have turned to some of the same methods to further their own causes, as Stephanie Mencimer outlined in her article for Mother Jones. The result has made "post truth" a recognized term, and growing political polarization an accepted reality. What is the remedy? Beyond increasing public access to quality education and strengthening other social institutions, we need a deeper understanding of the fundamental nature of truth, error, and how we can be led to either. That's fallibilism; that's semiotics. This is the terrain on which conflicts increasingly play out, so it's time to become familiar with it.

Illing, Sean How Russia pioneered “fake news” and then used it to sow chaos in America (2018)

Boston Globe, Lawrence Martin-Bittman (2018)

3.6 Neurofeedback (biofeedback) and semiosis

"By linking brain activity to an image or sound in real time, we can use simple game-like techniques to get people to train themselves to forge new neural connections and voluntarily adopt (or avoid) certain mental states. The fact that people can see and hear what their brain is doing provides a lever that allows them to internally regulate their own mind. With a map of an individual’s neural activity while thinking of a particular concept or phobia, it’s possible to give patients positive reinforcement when they manage to reduce activity in the areas of the brain that correspond to the experience of overwhelming fear. It can be effective even when participants aren’t aware of the goal of the procedure. New research shows it’s also possible to implant thoughts into people’s brains without them being aware of it. Referencing the Hollywood blockbuster Inception (2010), this is being called ‘incepted neurofeedback’. It has a potential dark side: the risk that neurofeedback could become a back-door for manipulating our brain states, without us even realising it. The clinical and ethical implications of such methods have barely been explored." And we can also use fMRI scans of brain activity to interpret what a person is thinking. This technology is only in an early stage but already surprisingly good. What are the full implications of laying bare our inner semiosis if we can 1) tell what people are thinking and then 2) control those same thoughts, and all without their being aware of it?

Kimmich, Sara, Brain, heal thyself (2019)

Greene, Tristan, Mind-reading AI isn’t sci-fi anymore. (2018)

Mok, Kimberley, Mind-Reading AI Optimizes Images (2018)

Rousmaniere, Tony, What Your Therapist Doesn’t Know (2017)

3.7 Conservatives, liberals, politics and semiotics

"People who are very conservative seem to have a much larger volume and a much more sensitive amygdala – the area of the brain that is involved in perceptions of fear. People who are more liberal seem to have a greater weighting on the region of the brain that is engaged in future planning and more collaborative partnerships. They seem less sensitive to immediate threats; instead, they are looking to the future. What we see in propaganda through the centuries is that if you heighten someone’s fear response using environmental manipulation, you are more likely to make them vote in a rightwing way." This reminds me of Jennifer Gabrys, who described the potential impact of her research in a 2014 paper titled "Programming Environments: Environmentality and Citizen Sensing in the Smart City" in which she utilizes the "governance through milieu" concept of Michel Foucault. Foucault himself borrowed the concept “milieu” from Georges Canguilhem. According to Canguilhem, the contemporary notion of milieu refers to relationality itself, where it is impossible to separate the object from its environment (that is, the systems of relations in which it is embedded and functionally dependent upon). The takeaway is that if you want to understand or influence something, no matter how big or small, then you must understand relationships.

A semiotic perspective effectively enables us to reinterpret traditional political power structures. Foucault once said "In political thought and analysis, we still have not cut off the head of the king." Since all forms of power are bottom-up, embodied in the style of everyday practices, the understanding of power as emanating from the sovereign or the state is incorrect. Consequently, in "Biopolitics 2.0", as Gabrys terms her particular version, the focus is less on governing individuals or populations and more about establishing environmental conditions in which responsive modes of behavior can emerge.

Tucker, Ian, Neuroscientist Dr Hannah Critchlow: ‘Changing the way that you think is cognitively costly’ (2019)

Element, Anthony, Liberals and Conservatives — they really are different (2013)

3.8 Applications: film and video games

All forms of entertainment involve semiotics. In video games every aspect of the game is designed to convey meaning. In movies like Arrival, Silver Linings Playbook, and Inception the dialogue, subject, or other aspects of the film explicitly or implicitly reference how we make sense of life and life events. If, as Peirce said, "all this universe is perfused with signs, if it is not composed exclusively of signs”, then to adopt the tagline from Dune, wouldn’t “he who controls the signs controls the universe”? In the movie Watchmen, “through Ozymandias (aka Adrian Veidt) Moore alluded directly to semiotics itself and to the ‘gordian knot’ quality of signs. The Gordian knot is also an allusion to the problems facing Adrian Veidt in his attempts at ‘untying’ the threat of nuclear annihilation in the world of Watchmen. Veidt is a watch-man in the sense that he watches a bank of simultaneously broadcasting television screens (whose channels randomly change every hundred seconds) that enable him to detect trends in our image saturated postmodern world [the zeitgeist].”

Touponce, William, Signs and Synchronicity in Watchmen (2006)

According to Yuval Noah Harari, “biotech and infotech” (by which he means algorithms, essentially) will remake our world. But he leaves out the ‘subject’ (subjectivity) in his discussion and is thoroughly within the ambit of Cartesian dualism. Signs (semiotics) are more fundamental than algorithms, and more complex as well. Algorithms may rule us and the world, and after a manner of speaking, they do. But they will never, alone, elucidate the how and why of it, we cannot figure out how or why this “ruling” is capable of occurring. For that we need a deeper understanding of subjectivity, and this understanding is afforded through semiotics (as best described by Pierce/Sebeok/Deely etc.) Infotech may rule, but semiotech will allow manipulation at a deeper level.

Q: But do we even matter to algorithms? You're on the human side of the equation in which what we think, what we need; our knowledge, our understanding, our... narcissistic prometheanism - our egoism of being at the center - our subjectivity is the all important thing. It's not! It thinks us, there is no subjectivity... we don't need to 'know'; maybe, as in Bataille, unknowing is what is important... or as in Deleuze/Guattari: delirium is all...

A: Of course we’re not at the center. Semiotics has moved outside of anthropocentrism, with the exploration of biosemiotics, and even hypothetical physio-semiotics, to name a few. Now regarding there being “no subjectivity“, one of the minimal criteria for subjectivity is a sense of “meaning”, that is to say, the ability for one thing to stand for another thing (to a third thing, or rather to the system for which such a connection is relevant). If you want to understand how “ruling” is capable of occurring, you have to understand why anything is relevant or rather why such “standing for” connections are made in the first place, hence the need to account for subjectivity and moreover to collapse the mind/matter duality.

3.9 Aikido and biosemiotics

This is "the martial arts principle or tactic of blending with an attacker's movements for the purpose of controlling their actions with minimal effort. One applies 'aiki' by understanding the rhythm and intent of the attacker to find the optimal position and timing to apply a counter-technique." To understand the attacker on must know their semiotic processes more intimately than they themselves do. This applies to politics as well as combat.

4. Marcello Barbieri's function metaphor

"If we generalize the concept of interpretation, why do we not say, following Taborsky (1999, 2002), for example, that any function f(x) = y is an act of interpretation, whereby the function “f” interprets “x” as representing “y”? In this way, all physical laws expressed by functions like f(x) = y would be processes of interpretation and, therefore, acts of semiosis. This point is important because Peirce himself embraced this view and concluded that semiosis exists everywhere in the Universe. We realize in this way that if we extend the concept of interpretation, we end up with a pansemiotic view not a biosemiotic one." However John Deely notes that Barbieri, with his views being a quintessence of the Enlightenment ideal, has imposed one of the last spells of positivism on biosemiotics.

Markoš, Anton, Biosemiotics and the Collision of Modernism With Postmodernity (2010)

5. Terrence Deacon

5. Terrence Deacon“Simple model systems provide a first step toward re-legitimizing the concepts of reference and significance that have so far been excluded from the natural sciences. Demonstrating that an empirically realistic simple molecular system can exhibit interpretive properties is the critical first step toward a scientific biosemiotic theory. A better understanding of how interpretive dynamics can emerge from simpler chemical and physical processes should also point to new ways to study biological, neurological, and even social processes.”9

Thermodynamics and functional relationships figure large in Deacon’s paper “Steps to a science of biosemiotics.” Here he combines the concept of entropy (as it is differently defined in thermodynamics and the information sciences) with issues of reference and functional significance and concludes that “biological evolution can be understood in terms of a process that tends to optimize the relationship between information and the work that it organizes to preserve itself” by utilizing a “capacity to interpret immediate physical conditions as representing other as yet unrealized possible conditions, or some phenomenon that is displaced in space, time, or abstraction.”

Kalevi Kull provides a useful critique of Deacon's book "Incomplete Nature." Kull writes: "I myself have a strong preference for describing and explaining biological matters in positive terms of what is present... Deacon would have to show much more clearly and precisely how approaching biological and psychic phenomena in terms of “absent contents” has specific explanatory advantages." The notion of "absent contents" is the fundamental shift in perspective that Deacon is advancing. It's very intriguing. But I agree that in order to be a rigorous explanation, it should be possible to translate these ideas into positive terms as well. It appears that this is in fact what Deacon does later in the book, and some of his papers published subsequent to it also point in that direction.

Daniel Dennett's review: "What is missing from the computational approach [aka the machine metaphor] now so dominant in biology and cognitive science? According to Deacon, it is, well, missingness. Absence does not just make the heart grow fonder; in many places at many levels absence marks the ultimately thermodynamic asymmetries that power evolution and life, and reactions to absence play the foundational causal role in mental phenomena. ...By divorcing information processing from thermodynamics, we restrict our theories to basically parasitical systems, artifacts that depend on a user for their energy, for their structure maintenance, for their interpretation, and for their raison d'être. ...[Deacon] digs deeper and reconstructs the arguments about the Second Law of Thermodynamics, drastically revising the standard (and woefully out-of-date) ideas about causation that bedevil many —but not all— thinkers today."

"[Incomplete Nature’s] radically challenging conclusion is that we are made of these specific absenses — such stuff as dreams are made on — and that what is not immediately present can be as physically potent as that which is. It offers a figure/background shift that shows how even meanings and values can be understood as legitimate components of the physical world." In Gestalt psychology this shift in perception determines which parts are identified as the figure, and which are the background. It fully depends on the observer and not on the item itself. How did you decide what is part of the figure and what is part of the ground? Deacon suggests that we need to recognize a causal role for absence, not just presence. Nonexistence is a defining property of life (and mind); we are shaped by absences. ...If I understand Deacon (and Hoffmeyer) correctly, we might say that semiotic relations are like the tiger represented by the negative space, the absential features, the background of this image.

6. A review of Dennett's review

“[Dennett] no longer believes that neurons work like computers! …The reason for this remarkable change of heart is that Terrence Deacon and others have convinced Dennett that the nature of neurons as entities with metabolism and a lifecycle is actually relevant to the way they work. …The implications are large; if this is right then surely, computation alone cannot give rise to consciousness!”

“I’m inclined to say Incomplete Nature is Deacon’s callout to the incomplete explanation of natural processes like metabolism. All science yields right now are rather simple mechanical descriptions that do not take into account all of the forces at the molecular level. Even the splitting and recombination of DNA can be described and mechanically-computationally manipulated by biologists without taking into account all of the actual physical forces at work at the molecular level. Even the words physicalism, computationalism and materialism still carry very mechanical baggage because they do not describe the forces at work; hence classical dualism gets invoked.”

7. Deacon and Tononi

“Information theory as a key to consciousness has a pedigree - David Chalmers (1996) admits thinking that such a theory could be constructed, and Giulio Tononi (2010) actually did construct one: an info-theoretic measure of consciousness that is fully formalized in discrete systems. But why is Terrence Deacon, an anthropologist, and Tononi, a psychiatrist, the only ones following this up?” Incomplete Nature is largely about how a refocus on absence (i.e. what's not happening) as a constraint can help to shed light on the processes of life. This seems to be a very different approach from Tononi, but aside from that (and a host of other ideas related to semiotics), it is true that both Deacon and Tononi address information theory from this same angle.

Max Tegmark's view has been described as information realism or structuralism, but it also sounds a lot like biosemiotics to me. A similarity that appears to be lost in most reviews of his books and articles (but not all those who have considered this possibility would agree). Here are a few interesting thoughts he expressed:

"We live in a relational reality, in the sense that the properties of the world around us stem from... the relations between these building blocks. ...Our brain may provide another example of where properties stem mainly from relations. According to the so-called concept cell hypothesis in neuroscience, particular firing patterns in different groups of neurons correspond to different concepts. The main difference between the concept cells for "red," "fly" and "Angelina Jolie" clearly doesn't lie in the types of neurons involved, but in their relations (connections) to other neurons." Source: Max Tegmark, "Our Mathematical Universe" 2014 (p267)

Tegmark is involved with Giulio Tononi's "Integrated Information Theory" (IIT) of consciousness, where its quality is given by the informational relationships generated by a complex of elements. (Tononi, 2004) At this point biosemioticians like Terrence Deacon might caution that IIT insufficiently accounts for certain material qualities (that are in turn influenced by thermodynamic conditions) that affect the relationships under investigation, but there is otherwise enough agreement to pursue a productive conversation. We do live in a relational reality. The question is whether the form of those relationships, as described, can account for the apparent phenomena of consciousness, an awareness of one's perceptual world, and an ability to productively engage with it. Semiotics is in a useful position to provide evaluative support and criticism of the results of theories such as IIT due to it's roots in logic, a subject closely allied with math and physics (Tegmark's fields of study), and it's efforts to provide a more complete definition of the concept of "information." The challenge for us in the Anthropocene is to understand the Earth as an ecosystem that integrates matter and energy dynamics reference and normativity, with information, communication and meaning. The eventual result of this effort, to paraphrase Lovecraft, is that the piecing together of such dissociated knowledge will open up a broader conception of reality (a "bigger physics," per Deacon), and of our position therein.

7.1. Terrence Deacon, Moving Naturalism Forward workshop (Oct. 2012)

"Right now I'm very much interested in rethinking the very concept of information. I think we have a remarkably powerful physical and logical theory of information that dates from Claude Shannon. But of course it has nothing to say about reference, has nothing to say about anything normative. When you provide information to me there's a normative feature there, and in biology our understanding of information both has reference and normativity. So the Shannon model is not good enough, and so I've been struggling to make sense of this idea in evolutionary biology, and I think it's really a crucial question and for the origins of life people. How is it that a molecule becomes about something? That's a really interesting question. I've been struggling with a way to think that through and to become formal about it, to really make it clear. What I think that relationship is, because I think it can be, has to be something that we can make sense of. So in this respect there's a couple of things that I first of all think to be the case, but I'm willing to be convinced of.

"Number one: I don't think brains are like computers. I've spent a lot of time with brains and they just don't look like computing devices to me, and yet I'm not saying that it's not a functionalist physical kind of story. I just don't think our understanding of computation is big enough to accomplish what we want to say about this. I'm really interested in how to expand that notion because I give all the meaning to my computer. My computer's like a car engine, but I've assigned various values to what it's doing and so on. If I'm a computer too, then who's assigning it? You know, you get the same problem - sort of running back, and back, and back. Now a number of people say "Oh no, it's just because we're now situated in the world." What? My computer is situated in the world, and certainly one that runs an arm in a factory is situated in the world. I don't find any reason to think there's somebody home there. I think there is something more that we have to deal with. I'm willing to be convinced that I'm just a computer and all this stuff is just running programs. That's one thing I'm willing to be convinced of, but I need to have good science that tells me how to think that through."

7.2 Terrence Deacon: Interview with Tom Palmer

In this video Deacon explores the relationship between evolutionary and semiotic processes and the emergence of end-directed processes in nature. This is how teleonomy sheds light on biosemiotics. If we can explain biosemiotics then we can better understand how and why we value the things we do. The utility of such knowledge would be immense.

"Minds have changed the causality of the surface of the Earth. Everything that is happening on the surface of the earth is radically different than it was before humans came onto the planet. Certainly before living things came onto the planet things were very, very different. Life changed the surface of the planet. We're now in the process of doing planetary changes without really being in control of it. That's because of minds, because of our ability to represent the world, to anticipate things, to think about how things work, to manipulate the physics." [This line of thinking, with still deeper roots of its own, is what led later to David Grinspoon's concepts of the "Sapiezoic" and "Terra sapiens."] "We recognize that the "hard sciences" view of the world leaves value out, leaves meaning out. Of course that's what we're missing in this whole process. And yet just trying to marry them back together has failed. We really can't say "Okay let's put a little mind in here, and then machines over here, and then the minds and machine will interact. We don't understand what the relation is between the mind stuff and the physical stuff, and that's what gets us into trouble.

"We of course constantly talk about values. We constantly talk about the value of the ecosystem, the value of each species, the value of diversity, those sorts of things. If the ecosystem gets hotter and hotter and hotter we worry about that, but we don't have a sense of how value comes into the world. There's a point in time at which mind, values, and morality came into the world. It emerges into the world, it's part of the world. Matter gets organized in such a way that that organization brings this about, and so the fact that we exist means that there has to be a real story to be told about us, that we did come about somehow. The key is to figure that out. The key is to figure out that, yes indeed our experiences our values are really part of the world, they come out of the world they're not something separate that can't be figured into the physics of the world. We need a bigger physics, so to speak, that is big enough to encompass what we are."

8. Information theory

“I didn’t like the term Information Theory. Claude [Shannon] didn’t like it either. You see, the term ‘information theory’ suggests that it is a theory about information – but it’s not. It’s the transmission of information, not information. Lots of people just didn’t understand this... I coined the term ‘mutual information’ to avoid such nonsense: making the point that information is always about something. It is information provided by something, about something.” [Interview with R. Fano, 2001]

8.1 Biosemiotics: more of a subject/information relation than a subject/knowledge relation.

Semiotics has been seen as a tool for approaching the epistemologic problems of biology. This has several dimensions. Firstly, biosemiotics seems to propose for biology a sort of philosophical basis or background. Secondly, it enables the introduction of subjectness, i.e. organism as a subject, into the biological realm. And thirdly, it helps to understand the development of mental features through the semiotically interpreted evolutionary epistemology. ...Eugen Baer said, “we must look at adaptation as a semiotic phenomenon, that is, as a process of signification.”

Source: Kull, Kalevi, Theoretical Biology on Its Way to Biosemiotics (2009)

9. Moiré patterns

“If a pattern is that which, when it meets another pattern, creates a third – a sexual characteristic exemplified by moiré patterns, interference fringes and so on – then it should be possible to talk about patterns in the brain whereby patterns in the sensed world can be recognized.” - Gregory Bateson (from a letter to John Lilly on his dolphin research, 10/05/1968, cited in “Upside-Down Gods: Gregory Bateson's World of Difference” By Peter Harries-Jones)

10. Machine semiosis

There is disagreement over the extent to which machines participate in semiotic processes. The discussion is very interesting. On the one hand, the popular materialist explanation is well represented by Marcello Barbieri, who wrote: "A computer has codes but is not a semiotic system because its codes come from a “codemaker”, which is outside it. This makes it legitimate to say that cells too can have a code without being semiotic systems. All we need, for that conclusion, is the idea that the genetic code was assembled by natural selection, i.e., by a codemaker that is outside the cell just as the human mind is outside the computer."

That’s an oversimplification as it ignores aspects of the extended evolutionary synthesis, like the Baldwin effect (teleonomy), but it is representative of such a perspective. Then we have the incremental semiosis views of Søren Brier, Winfried Nöth, and (probably) N. Katherine Hayles. Søren Brier (in "The Cybersemiotic Model of Communication") enumerated a five level schema that identifies levels of semiosis. In that paper Brier quoted Winfried Nöth (from "Semiotic Machines"):

“One could describe the operations of a digital computer merely as a sequence of electrical impulses traveling through a complex net of electronic elements, without considering these impulses as symbols for anything” ...What is missing for these signs to develop from dyadic to triadic signs is an object relationship. The dyadic relations are merely dyadic relations of signification, but there is no denotation, no “window to the world” which allows to relate the sign to an object of experience ...the messages produced by a computer in the interface of humans and machines are either messages conveyed by a human sender and mediated by the computer or they are quasi-signs resulting from an automatic and deterministic extension of human semiosis.”

That is apparently the view shared by Terrence Deacon and the majority of the biosemiotic community as well, that where human mediation is required, semiosis isn't really complete in a computer. This is an important point and probably the area of greatest inquiry in biosemiotics today. But semiotic machines are definitely a real possibility (if not already actualized). Gregory Bateson distinguished between systems capable of drawing distinctions (creatura) as compared to systems of purely mechanical interactions (pleroma). To him, “information” itself was a fundamentally relational concept – i.e., a “difference” between states of being that exists not “in itself,” but only such as is registered as relevant to the workings of a given system by that very system. These seem to be minimal requirements for machine semiosis, though Nöth likely elaborates further. We can turn to Rothschild, Dennet, and Einstein to see why such issues need to be addressed in any rigorous explanation of semiosis:

Friedrich Rothschild (1963) wrote that "The difficulties created by the categorical rift between manifestations of consciousness as against physiological brain processes cannot be solved by merely proclaiming a unity of body and mind. Nor will it suffice to view these two avenues of analysis as two aspects of a higher unity beyond the grasp of human understanding: the first, the anatomical and physiological analysis of processes occurring in the central nervous system, and the other,the introspective analysis of the consciousness. For once this formula is accepted, nothing prevents us from continuing in the style of the old dichotomy. Rather, it is necessary to introduce novel methods of thought based on the intimate connection of psyche and soma, rather than on their separation. For this purpose, the semiotic method is the only choice remaining."

Daniel Dennett’s (1992) “flight simulator video game” argument against the explanatory viability of a purely physicalist explanation of brain activity for understanding and explaining our experience of “mind”: Observing the activity of the electronic impulses taking place on the computer’s circuit board, no matter how minutely, will not reveal the relevant entities, categories, and relations that constitute the consequential semiotic products of those activities for the user of the software."

Albert Einstein observed that one could, if one wished, construct a graph of air pressures as away of “analyzing” the beauty and emotional power of a Beethoven symphony, but that one would thereby be ignoring the very thing that, in doing so, one first set out to explain.

|

| Michael Bergman, A Knowledge Representation Practionary (2018) |

This was the insight that Charles Sanders Peirce had about semiotic processes, later developed within biosemiotics by Sebeok, Hoffmeyer, Deacon and others. If these representations can be compared and distinguished by a system, then they are cognitive processes (per Hayles), and if these comparative distinctions are made according to their relevance to that same system, then they are semiotic processes (per Bateson), and lastly since consciousness is a semiotic relation (per Hoffmeyer), such a system displaying these traits would at some level be conscious.

The biological systems that we consider to be conscious display a degree of complexity far greater than artificial systems do at present. As Judea Pearl has noted, we currently have a limited ability to compare and distinguish representations computationally. Pearl specifically notes that the concept of causality is incompletely articulated. Without a rich computational toolset for interpreting immediate physical conditions as representing other as yet unrealized possible conditions, or some phenomenon that is displaced in space, time, or abstraction (per Deacon), the reach of machine semiosis will remain limited. But there is reason to suppose this will not always be the case. If machines do become capable of making the full range of distinctions, relations, and interpretations as humans, then the semiosphere will expand still farther. As Beever and Tønnessen write in Justifying Moral Standing by Biosemiotic Particularism: "If information and meaning are linked by semiosis, then the door is open to understand complex computational systems – from human minds to artificial intelligence systems – as semiotic and, in consequence (on some interpretations), morally considerable."

Karen Hao writes "For example, if you know that the shape of a handwritten digit always dictates its meaning, then you can infer that changing its shape (cause) would change its meaning (effect)." If we use deep learning to reveal not only why the world works the way it does, but also how meaning, or an interpretant, is generated from representamen, then watch out! The potential is great for both good if we shape them to promote the object of health, or ill if manipulated to undermine the same. Let's ensure goal alignment, to the extent that we are able. This is the intersection of semiotics and deep learning. Computers are improving their ability to understand how representations relating to other things can be interpreted. That’s big.

Hao, Karen, Deep learning could reveal why the world works the way it does (2019)

|

| John Flach, Supporting productive thinking (2015) |

Cornelis de Waal wrote: "The debate between nominalists and realists, a debate that according to Erasmus even led to fistfights among medieval philosophers, plays a prominent role in Peirce’s thought. Whereas the nominalist claims that only individuals are real, the realist holds that relations are as real as the individual objects they relate." That's a simplification of course, but a useful one nonetheless, with interesting implications. For example, the concept of causality specifies a dyadic relation between things, and notably Judea Pearl has claimed we are in the midst of a "causal revolution." In the same way, the concept of semiosis specifies a triadic relation between things. A few formal definitions have been proposed:

"We may define a cause to be... if the first object had not been, the second never had existed."Pearl, a computer scientist and philosopher, states that while the observational component of science has benefited from the power of formal methods, the design of new experiments is still managed by the unaided human intellect. But, when experimental science enjoys the benefit of formal mathematics along with its observational component, another scientific revolution will occur that will be equal in impact to the one that took place during the Renaissance. And AI will be the major player in this revolution. ...I suspect that, both causality and semiosis being relational concepts, their relevance for all forms of cognition, whether human, AI, or other, is critical.

- Hume (1748)

"A sign is something, A, which brings something, B, its interpretant sign determined or created by it, into the same sort of correspondence with something, C, its object, as that in which itself stands to C."

- Peirce (1902)

Terrence Deacon has added a new twist, when he wrote in the opening to his book Incomplete Nature: "A causal role for absence seems to be absent from the natural sciences." Relational concepts are not only lacking from computer science, but they are insufficiently understood within natural science as well. In "What is Life?" Erwin Schrödinger wrote: “Living matter, while not eluding the ‘laws of physics’ as established up to date, is likely to involve hitherto unknown ‘other laws of physics’, which, however, once they have been revealed, will form just as integral part of this science as the former.”

Charles Sanders Peirce: The Architect of Pragmatism (2003)

Reasoning with Cause and Effect (2002)

|

| Recursive normative triad, Marc Champagne (2011) |

Interpretation is ultimately a physical process, but one with a quite distinctive kind of causal organization: some favored consequence must be promoted, or some unwanted consequence must be impeded, by the work that has been performed in response to the property of the sign medium that is taken as information. This is why an interpretive process is more than a mere causal process. It organizes work in response to the state of a sign medium and with respect to some normative consequence - a general type of consequence that is in some way valued over others.

This allows causal linkages between phenomena that otherwise would be astronomically unlikely to occur spontaneously to be brought into existence. And this is why information has so radically altered the causal fabric of the world we live in. It expands the dimensions of what Stuart Kauffman has called the “adjacent possible“ in almost unlimited ways, making almost any conceivable causal linkage possible (at least on a human scale).

Source: Terrence Deacon, “Incomplete Nature,” (p392, 397)

Graphical/diagrammed semiotics and experimental semiotics. There are all sorts of diagrams, flow charts, and other graphical tools used within the disciplines of semiotics, logics, second order cybernetics, computer programming, epidemiology, symptomatology, and scenarios modeling. Deacon’s description of how the causal nature of interpretation involves normative consequences can also be represented in this way to help elucidate the connections involved.

10.3 John Flach and Cognitive Systems Engineering

"Peirce framed the problem of semiotics as a pragmatic problem - what is the capacity for humans to intelligently adapt to the demands of survival? How does our interpretation of a sign (e.g., pattern of optical flow) provide the basis for beliefs that support successful action in the world? The central question: How do we see the world the way it is?" John Flach is a cognitive systems engineer and provides a very useful perspective on semiotics in his recent work. He has a blog, academic papers, and a book he made freely available online. Of note, he takes an engineering approach to semiotics which is similar to the logical approach Peirce took, and that makes his interpretations particularly lucid. His applied semiotic diagrams are great, and it would be interesting to pair these with Marc Champagne's normative triad idea. In a pragmatic sense, I believe that application is the key to understanding in semiotics. Champagne places Ayn Rand within the Aristotle/Thomism/Deely tradition. This seems counterintuitive to me since by all accounts she espouses nominalist values rather than the realism of Poinsot and Peirce.

Flach, John, A Triadic Semiotics

Flach, John and Fred Voorhorst, What Matters? (2016)

Champagne, Marc, Axiomatizing umwelt normativity (2011)

“There is information in the light to specify affordances .... this radical hypothesis implies that the value and meaning of things can be directly perceived. The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal .... either for good or ill. By affordance I mean something that implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment. The notion that invariants are related at one extreme to the motives and needs of an observer and at the other extreme to the substances and surfaces of a world provides a new approach to psychology” (Gibson 1979: 179).

Pickering, John, Affordances are Signs (2007)

"Technology is a constructed extension of humanity's semiotic capacity... The technological age draws out the importance of connectivity and the notion of the human as the animal semioticum, the semiotic animal. Because of it's transcendence over subject and object, all semiotic relations per se are suprasubjective; the denial of semiosis leads to solipsism."

Richard Grablin, The Disconnected Connecting Self (2014)

Stephen Sparks, "Semiotics and Human Nature in Postmodernity: A consideration of Animal Semioticum as the Postmodern Definition of Human Being" (2010)

10.4 John Sowa, Mike Bergman, and Marvin Minsky on Peirce, AI, and "Thirdness"

Minsky: "I find most people say, well it’s either this or that and I’m always inclined to look for a third thing. Every now and then I get a new theory because I found that some community has gotten stuck making a di-stinction. The joke I made was that there’s no word – in English at least – for tri-stinction or trifference. Could you adapt Legos so that they had more triangular structures? Well then, it would be harder to make things at first, but easier later." Pierce's thesis is that all relations may be constructed from triadic relations, but monadic and dyadic relations are not sufficient. John Sowa agrees, and noted that in conceptual graph terms, it is trivial to show that there will always be one or more nodes in the graph with three or more attached arcs. That reminds me of the Tao Te Ching: "Tao produced the One. The One produced the two. The two produced the three. And the three produced the ten thousand things."

Mike Bergman writes: "While the current renaissance in artificial intelligence can certainly point to the seminal contributions of George Boole, Claude Shannon, and John von Neumann in computing and information theory (of course among many others), my own view, not alone, is that C.S. Peirce belongs in those ranks from the perspective of knowledge representation and the meaning of information." He describes what Deely termed "suprasubjectivity," in other words how Peirce provides perspective to dyadic structures: "A thirdness is required to stand apart from the relation, or to express relations dealing with relations." In his book "A Knowledge Representation Practionary: Guidelines Based on Charles Sanders Peirce" (2018) Bergman applies these insights: "A triple is a basic statement equivalent to what Peirce called a proposition. We often represent triples as barbells, with the subject and objects being the bubbles (or nodes), and the connecting predicate being the bar (or edge). This terminology is the language of graphs. As one accumulates statements, where the subjects of one statement may be an object in another or vice versa, we can see how these barbells grow linked together, wherein a single statement grows to become a longer story."

|

| Peter Harries-Jones, "Upside-Down Gods" (2016) |

Muz: "Explain what biosemiotics’ value is as a field, since you think people are misunderstanding it. If you think it is fact-based and worthwhile, could you say how?

Gerald Ostdiek: "The central idea of biosemiotics is that living things go about living by ‘reading’ what ‘signs’ they are able to discern from the environment. A ‘sign’ is that thing that stands for another thing to some living thing; signs are not limited to abstract symbolic constructs, but co-exists with every ‘minding’ – signs are inferred within every interaction in which some living thing is seen to extract awareness of some feature of its surrounds. (E.g., an amoeba swimming up a glucose gradient or a human getting directions to Brno from a roadside placard.) This not only informs the actions of the living thing and its individual development, but also serves as a factor of selection and evolution. The argument is that biological mechanisms are semiotically realized. If this is true, then we can expect to learn something (not everything, something) about biological processes by isolating and identifying various sign functions (as best we can, semiosis, like biology, is messy, irrational, and driven by history and need). This is neither limited to, nor eliminated by human culture: in my view (Deacon would agree, Barbieri would not), biosemiotic function is the ‘missing link’ between abstracted human constructions and the rest of nature; it eliminates the need for the ill defined philosophical concept of epistemology by memetic replication. I know of no-one who thinks that biosemiotics simply replaces the neo-darwinian synthesis; the argument is that it complements it. In addition to serving to isolate some specific factors of evolutionary and developmental biology, it also allows for a useful extrapolation from biological processes to human experience."

From a separate presentation: "Accessing the adjacent possible is necessary for biology because we have to see the future state of having a full belly. We have to see a possible future, a full stomach. This becomes a game in a technical sense that is played by all living things. For example one of my favorite examples of this has to do with a study that's been done repeatedly with foxes and rabbits where the fox is tracking a rabbit. A fox has to invest his energy wisely. He sneaks up. If the rabbit sees the fox before the fox gets to the rabbit the rabbit doesn't run away. He stands up on his hind legs and looks at the fox "I see you." And what does the fox do? Does he run real fast up to the rabbit? No, he goes around because the fox cannot manage catching a rabbit [without the element of surprise]. It doesn't fit the fox's past experience. And the rabbit doesn't want to run away because he knows he can escape."

11.1 Hares and Foxes

“Let us consider the hare-fox situation discussed by Anthony Holley (Holley 1993). A brown hare can run almost 50 per cent faster than a fox, but when it spots a fox approaching, it stands bolt upright and signals its presence (with ears erect and the ventral white fur clearly visible), instead of fleeing. After 10 years and 5000 hours of observation Holley concluded that this behaviour is energy saving: if a fox knows it has been seen, it will not bother to give chase, so saving the hare the effort of running. Holley rejects the alternative explanation, that the hares just want to better monitor the movements of their predators, partly because the behaviour does in fact not help them to see the fox more clearly, and partly because they do not react the same way to dogs. While a fox depends on stealth or ambush to catch a hare, the dog can run faster and it would therefore be counterproductive for a hare to signal its presence.

“The hare 'knows' that the fox has the habit of not chasing it if spotted. Thus it develops the habit of showing the fox it has become spotted. Whether this habit has become fixed in the genomic set-up of the hare or whether it is based mostly on experience is probably not known, but it doesn't matter much.

“It should be noticed that the fox profits from this communication as well since at least it spares the time and effort of trying to sneak up on the hare. So, this is actually a kind of mutualism, the whole situation presupposes the existence of a shared interpretative universe or 'motif', we might term it an eco-semiotic discourse structure (with a little help from Michel Foucault's concept 'discours', which very briefly stated refers to the symbolic order relating human subjects to a common world (Foucault 1970, Cooper 1981)). How much of this kind of semiotic co-operation goes on in nature? Probably we have only seen the beginning of these kind of studies, and it would be my guess that our present knowledge gives us only a small glimpse of a nearly inexhaustible stock of smart semiotic interaction patterns taking place at all levels of complexity from cells and tissues inside bodies up to the level of ecosystems.”

Source: Jesper Hoffmeyer, Biosemiotics: Towards a New Synthesis in Biology (1997)

|

| Karma incarnate, a hyperparasitoid (Piotr Naskrecki) |