|

| The Butterfly Dream |

"Man models himself after Earth. Earth models itself after Heaven. Heaven models itself after Tao. And Tao models itself after Nature." - Lao Tzu (Wing-Tsit Chan trans.)John Maynard Smith and Eörs Szathmáry in "The Major Transitions in Evolution" wrote that the inculcation of proper behavior is often achieved by ritual and myth. So that "throughout their lives, in speech, story, and song, all people sing the same tune" (Plato, Laws). To see an example of this, John Miller in his book, "A Crude Look at the Whole" writes that on the island of Bali, the need for coordinated cropping by farmers opened up "a niche for an elaborate religious institution with various shrines and temples tied to the irrigation systems." Joseph Henrich also described how religious rituals leveraged the reputations of prestigious individuals and created community bonds through synchronous movement, music, and dancing. This effectively standardized beliefs and increased cultural transmission across generations.

“Thus have I made as it were a small globe of the intellectual world, as truly and faithfully as I could discover.” - Francis Bacon (1605)

"You can't do much carpentry with your bare hands and you can't do much thinking with your bare brain." - Bo Dahlbom (unpublished, cited in Dennett, 2000)

"... one of the main functions of an analogy or model is to suggest extensions of the theory by considering extensions of the analogy, since more is known about the analogy than is known about the subject matter of the theory itself ... A collection of observable concepts in a purely formal hypothesis suggesting no analogy with anything would consequently not suggest either any directions for its own development.” - Mary Hesse (1952)

"Systems modelers say that we change paradigms by building a model of the system, which takes us outside the system and forces us to see it whole. I say that because my own paradigms have been changed that way." - Donella Meadows (Leverage Points)

Goal oriented processes, whether biological or social, are always made in reference to some kind of model, simulation, or semiotic scaffold, which corresponds with greater or lesser degree of accuracy to the world we inhabit. As Judea Pearl wrote in The Book of Why, "To speak of causality, and to interpret data, we must have a mental model of the world... Anytime you see a paper or a study that analyzes the data in a model-free way, you can be certain that the output of the study will merely summarize, and perhaps transform, but not interpret the data." According to Charlie Stross, “Consciousness seems to be a mechanism for recursively modeling internal states within a body.” Animals, such as humans, use their senses, their nervous system, to construct a model that allows them to optimize their living conditions. Philosophy is, in one sense, an attempt to “model the model”, and technology is providing us with a more direct route to do this via better sense data. These models are what we use to navigate and explore possibilities and understand our relationships. The so-called ‘simulacrum account of explanation’ suggests that we explain a phenomenon by constructing a model that fits the phenomenon. On this account, the model itself is the explanation we seek. It uncovers causal relations that hold between certain facts or processes. We spend a great deal of time building, testing, interpreting, comparing and revising these valuable tools. Think of models as gedanken experiments, parallel thought universes we can explore. They project complex objects onto a low-dimensional scale that allows us to extrapolate or interpolate within them. At some point extrapolations based on limited information will break down and result in paradoxes or conflicts. When this happens it becomes necessary to expose and then examine unconscious assumptions. Models are only models, not the thing in itself, so we can’t expect them to be truly right. But what’s amazing is how well they sometimes work.

From a semiotic perspective, we might say that models are an icon/index/symbol compound. The simplest models are primarily "rhematic iconic sinsigns", that is they are representations that stand for something else because they closely resemble its qualities. These simple models are among the least abstract of all signs. But metaphors, analogies, and models that have many interacting parts can become very complex, as in the case of mathematical models. Peirce held that mathematics is done by diagrammatic thinking, through the observation of, and experimentation on, diagrams. (Recently Arran Gare pointed out that Robert Rosen came to a compatible conclusion.) It is interesting to reflect how modeling, simulation, and mathematics have this close relationship and origin within foundational semiotic processes. Significant parts of scientific investigation are carried out on models rather than on reality itself because by studying a model we can discover features of, and ascertain facts about, the system the model stands for; in brief, models allow for surrogative reasoning. Once the model is built we have to use and manipulate it in order to elicit its secrets. Such dynamic models, which involve time, are simulations. From an anthropological viewpoint, simulations are often used to imitate 'real' events, people and things, ranging from rituals and objects representing supernatural entities and forces, to calendars, schedules, essay outlines, and computer simulations; they help us to ‘extend ourselves’, as it were. Humans, and indeed many animals as well, have used models and simulations (cosmologies, for example) for thousands of years to help us survive, understand the world, and order society. They are ubiquitous throughout history. Herbert Stachowiak postulated that “all cognition is cognition in models and by models”. Indeed, one's conscience or "inner voice" is itself a model that seeks to bring our actions in congruence with our thoughts. Paul Cobley, in Cultural Implications of Biosemiotics, wrote "Humans’ modeling explains the foundations of culture... ethics is a natural phenomenon arising out of human modeling." So it should come as no surprise that we need to engage with these cognitive tools all the more now. Historically, the level of engagement needed to sustain lasting change has only been achieved at the cultural level.

Let's explore the nexus between cultural anthropology (an enormously rich area) and modeling and simulation (also extensive). Gregory Bateson, Jesper Hoffmeyer, Jakob von Uexküll (umwelt), Robert Trivers, Terrence Deacon, and Joseph Henrich are just a few of the names who either have or are continuing to publish in this area. Doubtless many others are as well. But among these, who is applying this knowledge to contemporary problems in social and environmental health? To begin, let's consider how rituals, ceremonies, traditions, etc. within cultures function to provide an orienting cosmology which structures the physical and social lives of large numbers of people and influences the way we see things, our personalities, and our day-to-day activities in largely unconscious ways. So much so that when we sever ties to established traditional models and simulations, which can be a good thing to do insofar as they may be harmful, we also disrupt the beneficial regulation and cooperative capabilities that they have enabled.

Disruption comes with a cost, but it also offers an opportunity. New models and simulations can be created through an open process of discovery and a willingness to incorporate new knowledge and insights, as they arise. Since our point of view of things will always be rooted in a cultural model and worldview, we cannot float listless at sea for long. But disruption is coming hard and fast today. Social media, especially when manipulated against our will, has contributed to creating the conditions that have eroded confidence in any single model of reality, thereby handicapping our ability to address common problems and cooperate effectively. But in addition to harming us, these new tools, that are now a part of our cognitive assemblage, can also be used to improve models and simulations, as many researchers have shown (notably Alex Pentland in the "Red Balloon Challenge" contest, or the "Peacemaker" game for understanding complex conflicts).

Among these improved simulations are climate models that can accurately track numerous variables and generate startling predictions. Simply read one recent summary of this progress: “In the late 1970's, supercomputers performed about 16 billion computations a second. In contrast, the world's soon-to-be fastest computer coming online at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in 2021 will perform 1.5 quintillion computations per second. Not only will computers of the future be capable of processing information on everything from the upper atmosphere to ocean currents and all the details in between — such as sea spray, dust, ice sheets and biogeochemical cycles — but they will be able to do so while capturing the ways humans influence the climate and how climate change influences humans.” Zeke Hausfather, lead author of a study published Wednesday by UC Berkeley, MIT, and NASA, found that the majority of climate simulation models have accurately predicted global heating for the past 50 years. He said “It is impossible to know exactly what human emissions will be in the future. Physics we can understand, it is a deterministic system; [but] future emissions [also] depend on human systems, which are not necessarily deterministic.” This is important; we can model and simulate deterministic physical systems, such as the solar system, but the future depends upon how we interact with those systems, and that can always change.

|

| The Map is not the Territory. Harry Beck's map. |

The choices we make are determined by the mental models we hold in our heads for how things work. Instead of good or bad people, we have good or bad models for life and society which are shared through cultural transmission. The better these models are, the healthier our interactions with each other and the environment tend to be. Everyone gets a model handed to them at birth, and as they grow they decide in what ways to shape and change it, adding some things and modifying others. If a person starts off life with a very poor model, even though they may be a "good" person they may still make some bad choices with harsh consequences due to their faulty model. If they begin with a very good model, even if they are a "bad" person they may still make some good choices simply on the strengths of the mental model they inherited from others. Life is this process of continually refining our shared models and mental simulations of the world, upon which so much depends. Even our identities, our notions of who we are as individuals and hence our conceptions of well being, self worth, and how we relate to others, are formed based upon these models and simulations.

Maps and models

Schafer and Schiller write: “The brain builds, stores and uses mental maps. These models of the world enable us to navigate our surroundings, despite complex, changing environments—affording the flexibility to use shortcuts or detours as needed. Model building or mapmaking extends to more than physical space. Mental maps may exist at the core of many of our most “human” capacities, including memory, imagination, inferences, abstract reasoning and even the dynamics of social interactions, recording how close or distant one individual is to another and where that individual resides in a group’s social hierarchy. Biological relatedness, common group goals, the remembered history of favors and slights—all determine social proximity or distance. Relationships can be conceived of as coordinates in social space that are defined by the dimensions of hierarchy and affiliation. That the same mapping system may underlie navigation through space and time, reasoning, memory and imagination, and even social dynamics suggests that our ability to construct models of the world might be what makes us such adaptive learners. Fresh concepts can be related to older ideas. And a new acquaintance can reshape our social space. Models let us simulate possibilities and make predictions, all within the safety of our own heads, enabling us to navigate life itself.”

Models of Health

Too often people cause harm to each other and the planet we all have to share. A lot of the reason for that is people tend to get stuck in a way of doing things that might not work like it used to, if it ever worked well to begin with. We need to stop, and ask ourselves if it's time to change our habits, patterns, and models before they cause any more harm. An analogy would be a person who has a prediabetic condition. They have a mental model that tells them sugar tastes good. This model worked very well a long time ago when sugar was very hard to get. But today that's no longer the case. The store sells all the sugary drinks and ice cream we like to eat, and at affordable prices, so we can go there, buy it, and consume it daily. But now we know it's causing harm. Maybe our BMI has increased, and our metabolic functions are no longer normal. The doctor says we are on track for diabetes without a change of habits. Now we are faced with a choice. We can retain our mental model as is, and continue with our habits. A simulation based upon this model yields a predictable result when extended into the future. Or we can modify our models, avoid buying and consuming all that sugar, and forestall or even reverse our path to diabetes. We can go even further than that. If enough people realize the harm refined sugar is causing society in poor health and medical costs, we can make better regulations that reduce added sugar in foods, and make healthy alternatives more accessible and more affordable, and so on. Together we can update the models that society uses. This addresses the "evil" that has slowly crept into modern society due to placing the profit (generated from selling unhealthy products) over the well being of people. By promoting an improved model and simulation for how we want to live and conduct our lives, we can advance the public good, and make people's lives, including our own, better.

There are now very good scientific models incorporating knowledge of the myriad drivers of depression. Millions of people fight depression every year. With better tools for understanding how it works, we can prevent the loss of thousands to its tragic effects. We also have models for the stress response in humans, which is facilitated by the adrenal glands and controlled by a few cortical areas. This brain-adrenal connectome has implications for controlling cardiac funtion. Researchers have found that a chronic high level of daily stress releases cortisol into the bloodstream, a stress hormone that is particularly damaging to our delicate coronary artery cells.

According to the "medical model", medical treatment, wherever possible, should be directed at the underlying pathology. The biopsychosocial model later expanded this with a description of the complex interaction of biological factors (genetic, biochemical, etc.), psychological factors (mood, personality, behavior, etc.) and social factors (cultural, familial, socioeconomic, etc.), allowing for a broader intersection within the Nature versus Nurture debate. For any given pathology, which of these factors should be addressed? For example, a person may have a genetic predisposition for depression, but he or she must have social factors such as extreme stress at work and family life and psychological factors such as a perfectionistic tendencies which all trigger this genetic code for depression. Similarly in discussing climate change, we tend to focus on one or two contributing factors, such as the material conditions, while ignoring or minimizing the contribution of cultural, psychological, and philosophical factors. It’s time to reconsider our climate recovery model.

Models of pandemics

Dennis Carroll spent years studying infectious diseases. He formed a USAID program called PREDICT, where he guided research into viruses hiding and waiting to emerge. As he describes it, "PREDICT was a beautiful project. It was scientifically well executed. It was forward-leaning. But its scale was small. It discovered slightly more than 2,000 viruses. If you’re going to have a public health impact, finding 2,000 viruses out of a pool of 600,000, over 10 years, isn’t going to transform your ability to minimize public health risk. And PREDICT didn’t really navigate the second step in a critical equation—turning science into policy. We didn’t design it for that purpose. Also, even an annual budget of $20 million is not sufficient. You’d need about $100 million a year to carry out the kind of global program that would give us evidence to transform how we think about viral risk and how we should prepare for it. That’s what my new Global Virome Project aims to do. ...I’m an internationalist. Figure out how to care for our people. Pay attention to communities around the world that need assistance. We’re all part of the same ecosystem. This is a global issue. We either prepare for it and respond to it in the context of a global lens, or we don’t. If our preparations and responses are country-centric, we’re in for some serious trouble." (You can see Carroll in the Netflix documentary series "Pandemic".) Current models and simulations of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 predict several possible outcomes.

Epidemiological models and political games

An article in The Atlantic today reports "Epidemiologists routinely turn to models to predict the progression of an infectious disease. But sometimes people get mad when those models aren’t crystal balls. Why aren't they snapshots of the future? They describe a range of possibilities that are highly sensitive to our actions. So when an epidemiological model is believed and acted on, it can look like it was false. The range of predictions all depend on how people react. That such a variety of potential outcomes can come from a single epidemiological model may seem extreme and even counterintuitive. But that’s an intrinsic part of how they operate, because epidemics are especially sensitive to initial inputs and timing, and because epidemics grow exponentially. So if epidemiological models don’t give us certainty—and asking them to do so would be a big mistake—what good are they? Epidemiology gives us something more important: agency to identify and calibrate our actions with the goal of shaping our future. We can do this by pruning catastrophic branches of a tree of possibilities that lies before us. Models provide a way to see our potential futures ahead of time, and how that interacts with the choices we make today. Sometimes it looks like we overreacted. A near miss can make a model look false. But that’s not always what happened. It just means we won. And that’s why we model.

Rogers and Molteni describe how federal agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health have modeling teams, as do many universities. Since the 2009 outbreak of H1N1 influenza, researchers worldwide have increasingly relied on models and simulations informed by what little data they can find, and some reasoned inferences. But the ongoing catastrophe of testing for the virus means that no researcher in the United States has an overall number of infections that would be a reasonable starting point for untangling how rapidly the disease spreads. As with simulations of Earth’s changing climate or what happens when a nuclear bomb detonates in a city, the goal is to make an informed prediction—within a range of uncertainty—about the future. In the case of Covid-19, responding to those models may yet be the difference between global death tolls in the thousands or the millions. While our current models are imperfect, they’re better than flying blind—if you use them right. That's the key. Unfortunately, just as happens with models of climate change, the presentation of a range of possible futures in epidemiological models provides a lever for political opposition.

"After Governor Andrew Cuomo based a request for tens of thousands of ventilators on model projections, the president told television personality Sean Hannity, “I don't believe you need 40,000 or 30,000 ventilators.” He based that opinion, he said, on “a feeling.” Lisa Brandenburg, president of the University of Washington Medicine Hospitals and Clinics, would take the models over a feeling any day. Even before Covid-19, scientists had trouble getting policymakers to pay attention to their warnings. Now they can’t get enough data to make those warnings specific, and politicians are working to undermine what little the scientists are sure of. What was already a tragedy has evolved into a disaster, reaching toward catastrophe. And all of it was predictable."

Challenge prevailing beliefs

The Monthly Review writes: “Other than describing the wild food market in the typical orientalism, little effort has been expended on the most obvious of questions. How did the exotic food sector arrive at a standing where it could sell its wares alongside more traditional livestock in the largest market in Wuhan? ...Models such as the Imperial study explicitly limit the scope of analysis to narrowly tailored questions framed within the dominant social order. By design, they fail to capture the broader market forces driving outbreaks and the political decisions underlying interventions.” This is why we must interrogate our models. For if we do not, history will surely repeat itself.

From the Guardian: “Most leaders lack the discipline to do routine risk-based horizon scanning, and fewer still develop the requisite contingency plans. Even rarer is the leader who has the foresight to correctly identify the top threat far enough in advance to develop and implement those plans. ...But the Trump administration’s unprecedented indifference, even willful neglect, forced a catastrophic strategic surprise on to the American people. The White House detachment and nonchalance during the early stages of the coronavirus outbreak will be among the most costly decisions of any modern presidency. These officials were presented with a clear progression of warnings and crucial decision points far enough in advance that the country could have been far better prepared. But the way that they squandered the gifts of foresight and time should never be forgotten, nor should the reason they were squandered: Trump was initially wrong, so his inner circle promoted that wrongness rhetorically and with inadequate policies for far too long, and even today. Americans will now pay the price for decades.”

Models respond to salient features

As Aaron Bernstein pointed out, "if we want a robust response to a pandemic, we have to have the systems in place to do that". And as Jamie Margolin points out, the pandemic is proof that we can mobilize. We can quickly switch from a BAU model to a model which understands humanity is facing a common threat that doesn’t respect national boundaries, a model that values preparedness and a rapid response. This is the kind of model we need. The question Margolin asks is: Why didn’t we get it earlier? That likely depends on what we, individually and as a society, consider to be the salient features of our environment. Perhaps human evolution didn't adequately prepare us to respond to threats like climate disruption. There were few opportunities to understand the dynamics of climate change, properly appreciate the danger it represents, or practice a coordinated and effective response. Now compare this to our ability to recognize the signs of disease, which seems to trigger an immediate and automatic fear response. Transposing the response we have to a pandemic and applying it to climate disruption rests entirely on the strength of the analogy we can make between the two. If we leverage a sort of “pandemic model" of climate disruption, perhaps we can tap into this intuitive existential dread, and by adapting a “pandemic response template” for developing the social institutions and systems we need to tackle climate change, maybe we can improve our effectiveness in addressing these environmental problems. After all, evolution constantly appropriates body parts evolved for one purpose and adapts them for another (gills become mouths, legs become wings, etc.), so modifying social models by way of analogy seems entirely natural (pandemic response becomes climate response). It certainly helps that we now have the proof that rapid global behavioral change is possible.

Substance abuse, health care: facts and models

If we want to achieve meaningful goals, we need good models, and if we want good models, we need reliable facts. Einstein showed that no sequence of events can be metaphysically privileged – can be considered more real – than any other. But we have even more immediate concerns to address than investigating the limitations of metaphysics. At the 2020 Health Summit in Anchorage this week Alfgeir Kristjansson's presentation referenced the “social determinants” of health (SDOH), which do not receive enough attention, and Anthony Iton's excellent presentation. Preventing a problem always makes more sense than treating it later. Here are two examples. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in America, but many people with a low ejection fraction (EF) can improve it through exercise and other lifestyle changes. It is thought that the survival of preindustrial humans depended on moderate-intensity, endurance-like activity (e.g. hunting, gathering, and then farming). Research published in a 2019 paper titled "Selection of endurance capabilities and the trade-off between pressure and volume in the evolution of the human heart" provides evidence that the human heart in fact did evolve for this purpose (see also the "endurance running hypothesis"). Lifelong low blood pressure appears to be partly sustained by regular moderate-intensity endurance physical activity, whose decline in postindustrial societies likely contributes to the modern epidemic of heart disease. Kristjansson's presentation, however, addressed the Icelandic model for reducing substance use among teens. They focused on prevention rather than treatment, and abuse rates plummeted dramatically. "If the Icelandic model was adopted in other countries, it would benefit the general psychological and physical well-being of millions of kids, not to mention the coffers of healthcare agencies and broader society." Understanding the facts related to the SDOH, and using the appropriate models once these are uncovered, remains a significant challenge in much of the world today.

More Applications:

In a recent interview, Naomi Klein pointed out that although there had been widespread dissatisfaction within society, popular movements like Arab Spring and Occupy did not generate the kind of social changes their members aspired to because there wasn't "a clear demand of what the alternative to this failed model is". She went on to say "I think that in the intervening years so many people who are part of those movements have taken the responsibility of coming up with an alternative vision on an alternative plan really seriously. So now when we have one of those tipping moments I don't think we are going to make the same mistake of opening up a vacuum that somebody else can exploit". If social change is to be real and lasting, we cannot avoid engaging with these models. Revolutionaries of all kinds throughout history have advocated the adoption of alternative models, and their success is generally improved when such models are carefully thought out. Revolution without an alternative model, however, tends to simply perpetuate the conditions that generated discontent to begin with.

Greta Thunberg sees the world through a different model than most of us do. Combine that with a supportive family and community, access to rich educational resources, the use of effective messaging and media attention, and a public audience ready and eager to hear her and her message, she quickly catapulted into the international spotlight. What scares the powerful most of all is her tenacious and uncompromising vision of a different way of living, which is justifiably critical of the contemporary model: “I couldn’t understand how that could exist, that existential threat, and yet we didn’t prioritize it,” she says. “I was maybe in a bit of denial, like, ‘That can’t be happening, because if that were happening, then the politicians would be taking care of it.’” Thunberg’s Asperger’s diagnosis helped explain why she had such a powerful reaction to learning about the climate crisis. Because she doesn’t process information in the same way neurotypical people do, she could not compartmentalize the fact that her planet was in peril. ...Some of her opponents have attacked her personally. So many people have made death threats against her family that she is now often protected by police when she travels. But for the most part, she sees the global backlash as evidence that the climate strikers have hit a nerve. “I think that it’s a good sign actually,” she says. “Because that shows we are actually making a difference and they see us as a threat.” One model is being succeeded by another.

|

| Computational science |

Education can often serve to amplify our predispositions, at least when we reason like lawyers and less like scientists. In regard to climate change, it's been shown that the more education that Democrats and Republicans have, the more their beliefs tend to diverge. This appears to ignore exactly what that "more education" consisted of. For example, was it a degree in business, politics, engineering, ecology, physics, etc.? And what was the actual percentage of individuals who are on either side of the divergence? In the case of climate scientists, they diverge with over 99% supportive of the consensus and less than one percent disagreeing. That suggests to me we can conclude education has a net positive effect on our ability to think through questions effectively and arrive at factual conclusions. However it is when facts conflict with the models of reality that we tend to hold without reflective consideration that we are more likely to reject or distort information. We want new knowledge to conform to our preferred worldview, but effective thinking involves critically testing these models. If they are not subject to possible revision, we cannot think rationally.

As Howard Gabennesch pointed out, since our knowledge on any subject is fallible, incomplete, and subject to change, when we use our models and simulations, we do so with the understanding that these are provisional (this is the key to skeptical, critical thinking skills). Keeping this in mind, recently Vincent Liegey said “It is interesting to analyze how GDP became a religion: A central tool used by politicians, states, economists and by a lot of journalists – like a totem. Like something that should measure what is a successful or unsuccessful society or life.” We have seen how the religious promotion of GDP and market fundamentalist polices above issues of environmental and social justice have exacerbated climate change. This model is simply no longer tenable as it exists today without risking significant future harm. So have we forgotten that economic models are provisional? Even religions can, and often do, change when it’s time for a better model.

Today the calls for system change are everywhere; people feel fearful, insecure, and anxious. In a recent interview, Jason Moore said we need to ask questions that connect oppression, sustainability, and the political economy of capitalism. Models of "environmental holism" and "social holism" have always excluded a lot. But now we're at a moment when we can begin to put these together within a larger, expanded framework. (From this perspective that he notes the phrase “anthropogenic climate change” is really just blaming the victims of exploitation, violence, and poverty. More accurately, we are experiencing a “capitalogenic climate crisis”.) Systems theory views the world as a complex system of interconnected parts. One can make simplified representations (models) of the system in order to conceptualize it and to predict or influence its future behavior. Systems modeling is used both in engineering and in social sciences to define the structure and behavior of systems. In "Wall Street Is a Way of Organizing Nature: An Interview with Jason Moore", Moore describes the growth and influence of capital accumulation:

Capitalism is the gravitational field within which the “big picture” historical movements of the past five centuries have unfolded, and at its vortex is the commodity. Capital accumulation survives by turning the rest of the world into a commodity, a vast storehouse of interchangeable parts. In doing so, it undermines the very webs of life that sustain its project. The accumulation of capital doesn’t explain everything, but it’s hard to say much about the history of the past five centuries without understanding the contradictions of accumulation. Civilizations long before capitalism expanded across space, and drew in vital resources necessary for war, commerce, and culture. Resource frontiers are an enduring feature of human civilization. For all their variation, there was a common dynamic. Populations grew within established zones of settlement leading to various overflows of people into new frontiers. Commerce then followed these settlement frontiers. With the rise of capitalism after 1450, however, we see something radically different. We see a shift from resource frontiers to commodity frontiers. Instead of commerce following people as had been the case in premodern civilizations, people now followed the commodity. Financialization, shifts in family structure, the emergence of new racial orders, colonialism and imperialism, industrialization, social revolutions and workers’ movements – these are all world-ecological processes and projects, all with powerful visions for re-ordering human- and extra-human natures. Wall Street is a way of organizing nature, differently but no less directly than a farm, a managed forest, a factory, a market, a financial center, or an empire. Capitalism, in other words, does not have an ecological regime; it is an ecological regime.

|

| Address root causes or symptoms? |

At the end of the day, reality has to be the ultimate test, not “fairy tales of eternal economic growth”, as Greta Thunberg put it. Any model that places the economy at the top of the food chain, where the sole purpose of the environment is as an input to production, and it is assumed that growth will translate to benefits for all, is incapable of responding to environmental crises. And so such a model must be restructured or replaced. This is why Stiglitz is suggesting a rather modest adjustment to capitalism: change our primary measurement tool. Will that alone be sufficient to place the economy in its proper role, dependent upon society and the natural world (instead of the other way around)? Of course not. But this is an important first step. As Foucault once wrote “In political thought and analysis, we still have not cut off the head of the king.” In economic thought and analysis, GDP is still the king. We have not done our job yet.

In 1972 the first edition of "The Limits to Growth" analyzed the environmental sustainability problem using a system dynamics model. The widely influential book predicted that the limits to growth on this planet will be reached some time in the 21st century, largely due to the effects of systemic resistance to change. Sources of social resistance included pursuing narrow national, corporate, or individual self-interests (reflected in values, habits, and mental models). This resistance further decouples the human system from the greater system it lives within: the environment. If we use structural modeling to discover systemic root causes for both the change resistance and proper coupling subproblems, then higher leverage points for resolving them can be found. Solutions then push on these leverage points in the system. Engaging with these cognitive tools at the level of cultural models can uncover the root of the paradigm of unlimited economic growth and exploitation, allowing us to transition from an "expand, conquer, consume" mentality to a sort of "contract, cooperate, cultivate" story of living in harmony with the Earth, as promoted by ecological civilization. There are many other alternative models (such as the slow movement and degrowth). How do alternative models function? What can we learn?

When employers seek to consistently exclude any consideration of basic human needs, what kind of model and simulation are they running within corporate HR? How can they change? (Perhaps they can begin by reading Michael Ende's book Momo.) The bottom line is that their models are far too narrow. It may appear that they are improving their competitiveness within a cutthroat business marketplace, but the corrosive effects these practices have on the larger society suggest they are also taking us down a dark path. We can't ignore this. Gabriel Winant's article describes how many employers now “demand a workforce that can think, talk, feel, and pick stuff up like humans—but with as few needs outside of work as robots. They insist their workers amputate the messy human bits of themselves — family, hunger, thirst, emotions, the need to make rent, sickness, fatigue, boredom, depression, traffic...”

Some models are better than others

In "The Secret of Our Success", Joseph Henrich wrote "once humans became good cultural learners, they needed to locate and learn from the best models". In this context, he is referring to the skilled members of one's social group. (Who are your role models?) In "Solving for Pattern", Wendell Berry quoted Sir Albert Howard when he said that a good farm is an analogue of the forest which “manures itself.” A good farm is modeled on nature, as is the development of an ecological civilization. Nature is perennially viewed to be the best model we have. Slavoj Zizek, in the article Defenders of the Faith, wrote "More than a century ago, in "The Brothers Karamazov" and other works, Dostoyevsky warned against the dangers of godless moral nihilism, arguing in essence that if God doesn't exist, then everything is permitted... This argument couldn't have been more wrong: the lesson of today's terrorism is that if God exists, then everything, including blowing up thousands of innocent bystanders, is permitted — at least to those who claim to act directly on behalf of God, since, clearly, a direct link to God justifies the violation of any merely human constraints and considerations." (To balance that out, it’s important to point out that “engaged spirituality” has been a positive influence when we consider Ruskin, Tolstoy, Gandhi, MLK, and Thich Nhat Hanh.) In 2013 David Simon gave a presentation at the "Festival for Dangerous Ideas." We can end war if we wanted, all we have to do is end the monetization of our legislative branch (what others call a "dollarocracy" - one dollar one vote) so we get real effective democratic representation in government instead of (what David Simon calls) our currently inert government.

Chris Fisher wrote, “As archaeologists, we are trained to be time travelers: imagining the world as it existed in the past, seeing the world as it is today, and modeling change into the future. We are the ideal scientists to build an Earth Archive as a legacy for future generations. Those future generations will have different technologies and tools at their disposal, and will want to ask different questions. No one knows exactly how they will use this data, but it will surely be useful.” If we ask which models and simulations are meaningful to ourselves alone, but go no further, the real value and potential is lost. The question is, which of all these models and simulations are most meaningful to others? Which of these are meaningful within our larger associations? Where do they coincide and where do they diverge? Only by carefully studying and learning these things, only by seeing through the eyes of another, by viewing the world as those who have cared for us and whom we care for in return, will we discover what is truly meaningful. So here's a second experiment in trying to promote greater interaction and engagement with "modeling and simulation" tools (in addition to the DIY carbon tax described above): identify the models we use, what they consist of, where these coincide with and diverge from each other, and how they influence our relationships.

This takes us back through cultural anthropology and the significance of "mindreading" in the evolution of our species. "According to the 'Deep Social Mind' theory, humans have become cognitively adapted to reflexivity and intersubjectivity: as a species, we are well-adapted to read the minds of trusted others while at the same time assisting those others in reading our own minds. I read your mind as you are reading mine. Therefore, between us, we can gain an awareness of our own minds as if from the outside: my mental states as these are reflected in yours and yours as they are reflected in mine. In that sense, if this argument is accepted, our minds mutually interpenetrate. 'Mind' in the human sense is not locked inside this or that skull but instead is relational, stretching between us." But why this "enactive" process of co-production? Some have speculated a deceptive, indeed "Machiavellian" purpose behind this evolved capacity to read minds, which would improve our ability to manipulate others. But the cooperative benefits are equally apparent. The implications for interpenetrating models and shared simulations are profoundly important, and should be made more explicit for applications of cultural anthropology to contemporary global issues.

|

| A worldview |

Robert Rosen argued that mathematics should be understood as a way of modeling, and modeling is really only a special instance of analogical thinking, ubiquitous in everyday life. Modeling, Rosen argued, "is the art of bringing entailment structures into congruence". He continued, "It is an art, just as surely as poetry, music, and painting are. Indeed, the essence of art is that, at root, it rests on the unentailed, on the intuitive leap". (Rosen 1991, p.152) Rosen highlighted the central place models have in all living systems, including societies where models are central to defining themselves and their place in the world. Once this is understood and it is appreciated that with life, including all human organizations, modeling is ubiquitous, Rosen's work on modeling should be seen as relevant to societies and the functioning of democracies. What is required is an interrogation of the models that societies have of themselves and their relationship to their ambience or environments.In The Diversity of Life (1992), Edward O. Wilson wrote, "The best of science doesn’t consist of mathematical models and experiments, as textbooks make it seem. Those come later. It springs fresh from a more primitive mode of thought, wherein the hunter’s mind weaves ideas from old facts and fresh metaphors and the scrambled crazy images of things recently seen. To move forward is to concoct new patterns of thought, which in turn dictate the design of the models and experiments.” And Philip Henshaw, in Life’s Hidden Resources for Learning (2008), describes how, instead of taking our abstract models as reality or discarding them, we should be using these to reveal life. As he put it, after you adopt your model, keep both your model and observations going side by side. Then it becomes a sensitive detector of differences and can highlight the life around you. This continues the creative thought processes that occur when we first ‘make sense’ of things. (Interestingly, Henshaw is highly critical of the idea that the engine of evolution is the struggle for survival. He argues that organisms for the most part are "engaged in resourceful exploration, using what they find while avoiding conflict".) It is because our models so deeply influence society that understanding their origins and limitations is all the more important.

It is not only the sciences that are dominated by assumptions deriving from Newtonian scientific models, these assumptions dominate economics, as a consequence of which societies have acted on and continue to act on fundamentally defective models of themselves. It is through reformulating their models that societies form and transform themselves, and Judith Rosen in her preface to "Anticipatory Systems" pointed out that this is now essential if we are to work out how to choose "the most optimal pathways towards a healthy and sustainable future".

Expectation, Anticipation, Prediction

In “Expecting the Earth: Life, Culture, Biosemiotics”, Wendy Wheeler wrote: “The biosphere, as well as the semiosphere, is built upon expectations. One important meaning of legs (i.e. their function) is 'for walking'. The child in the womb has never walked, yet biological life incorporates into its processes legs and the expectation of precisely such a relation with the Earth yet to come... Expectations are an important part of what it means to be alive. No life walks or crawls or swims around expecting nothing. We all expect the Earth to be there when we put a foot out to walk or a fin to swim. We all expect the air to be there to breathe each day... In what more detailed sense might it be right to say that we, and all living organisms, are 'expecting the Earth'? What sort of expectations might this involve?"

Postscripts:

Treat the disease while you manage the symptoms

Our models of the world are inducing so much anxiety that we are increasingly turning to the support of organizational aids to manage our lives and coordinate with others. Why? Examples given in this article include tracking New Year’s resolutions, classes, jobs, assignments, deadlines, chores, self-care, fitness goals, and family events. None of these are by any means “new”, perhaps the only thing that may be new is the perfusion (or illusion) of choices that are now available. It is good to be organized, but we need to treat the disease and not just manage the symptoms. Emma Lee said “Planning has changed my life for the better. I write a lot more, I think more clearly, I’m more emotionally stable. It’s made a huge impact on everything.” Gretchen Klobucar said “People come to [planning] for a variety of reasons. In most cases, they’re seeking to manage a role or expectation they’re anxious about. They want to be able to plan so they can live the life they envision.”

Models of proper mental hygiene

Jim Kwik highlighted how the form of the media we consume influences our mental states: “When you wake up you’re in this theta alpha state and you’re highly suggestible. Every like, comment, share, you get this dopamine fix and it’s literally rewiring your brain. What you’re smart device is doing especially if that’s the first thing you grab when you wake up and you’re in this alpha theta state, is rewiring your brain to be distracted.” As Srinivas Rao explains: "You can either start you day with junk food for the brain (the internet, distracting apps, etc) or you can start the day with healthy food for the brain (reading, meditation, journaling, exercising, etc). Don't create a self imposed handicap. A few simple recommendations: Don’t use your devices in the morning, set aside 20 minutes to meditate, and focus an hour a day on uninterrupted creation time." Interestingly, many productive people follow similar advice. Karl Friston, for example, "does not own a mobile phone, and though he's very active on email within certain hours of the day, he limits other forms of electronic access, and generally does not utter a word before noon. He protects his time by “sticking rigidly to a diary, and making sure that there's somebody else in charge of the diary who knows the formula and can regiment it.” Regimented routine is his way of creating a cocoon around himself despite all these demands on his time—a Markov blanket, he calls it—in which to minimize the free energy of distractions, complexity, and avoidable uncertainty. Our growing impatience and distractibility are failed adaptations to the growing uncertainty of a world filled with more information than we can metabolize."

Mind over Matter

What is the effect of our mind on our bodies? The mind has a propensity to make predictions, and then ensure those predictions come to pass. “This [idea of expectation-based bodily response] is an evolved mechanism that allows us to capitalize on untapped resources at critical points in our existence,” Christopher Beedie says. The chemistry of expectation and belief is also the world of placebo, which is the effect of one’s beliefs on their body. These effects are chemical, employing things like dopamine, endogenous opioids, serotonin, and other chemicals your brain keeps on hand in case it needs to adjust what’s happening in the body. In his book, Suggestible You, Erik Vance talked to scientists around the world who investigate placebos, internal pharmacies, hypnosis, and the power of belief on the body and mind. One of his favorite quotes came from Alia Crum, a psychologist at Stanford. “I don’t think the power of mind is limitless,” she said. “But I do think we don’t yet know where those limits are.”

Reactance and Comparative modeling

DJ Khaled, the one-man internet meme, is known for warning his tens of millions of social media followers about a group of villains he calls “they.” “They don’t want you motivated. They don’t want you inspired,” he blares on camera. “They don’t want you to win,” he warns. But who are they? Like so many things, reactance is a double edged sword. We definitely must react, so long as we know who the real enemies are. Eliciting reactance has been used successfully in public health efforts, so I wonder: How can reactance be used effectively in climate change and other environmental efforts, which lie at the root of all public health? To me "they" are the models premised on myopic greed and ignorance. They lie in wait, ready to insinuate themselves into our lives and communities when we let down our vigilance. And they become more clear when we engage in comparative scenarios modeling. I can briefly sketch the sort of behavior model we would like and compare it to the problematic model that we find ourselves within, bringing the contrast between the two into stark relief. This illuminates who "they" are and allows us to confront them. Comparative modeling can also help identify models with less temporal discounting and those that promote greater shared experiences of social value.

Mental models and mindfulness

In their paper Mindfulness: A Proposed Operational Definition the authors write: "Much of cognition occurs in the service of goals, comparing what is with what is desired, and much of our thoughts and behaviors function in the service of reducing any discrepancies. When there is a discrepancy, negative affect occurs (e.g., fear, frustration) setting in motion cognitive and behavioral sequences in an attempt to move the current state of affairs closer to one’s goals, desires, and preferences. If the discrepancy is reduced, then the mind can exit this mode and a feeling of well-being will follow until another discrepancy is detected, again setting this sequence in motion. When goals cannot be met, and especially if the goal is afforded high value, then the mind will continue to dwell on the discrepancy and search for potential strategies for avoiding anticipated future negative events. This can lead to the maintenance or heightening of anxiety and escalate a spiraling cycle of dysphoric affect that can eventually lead to a major depressive episode. Rumination will continue until the person either satisfies or gives up the goal. Thus, disengaging from one’s goals [by establishing a reflective self awareness] should facilitate a release from ruminative thinking and thereby reduce vulnerability to certain forms of psychopathology." As Thomas Metzinger said, we should not be forced to consciously identify with thwarted or frustrated preferences via models from which we cannot effectively distance ourselves (and interrogate if need be, whether these models are personal or suprapersonal).

This is where comparative modeling, which Robert Rosen discussed at length (he called it the "modeling relation"), can address these forms of psychopathology. Rosen argued that modeling "is the art of bringing entailment structures into congruence", which is to say that it is all about reducing discrepancy. When we compare "what is with what is desired", we are comparing two different systems, reality and our desired model of reality. What the paper's authors suggest is that since the discrepancies we observe by means of this comparison can lead to anxiety, rumination, and depression, the mindfulness approach of recognizing and accepting these mental events as comparative modeling processes can be therapeutic. In order to reduce the anxiety I expose myself to, I need a position from which to manage the discrepancy between "what is" and "what is desired". The process for exploring counterfactual scenarios, and possibly later adopting them, begins by comparing at least two different models: a control model consistent with current patterns (what is), and one or more introduced new models congruent with a goal (what is desired). I can then ask myself the question: "What if, instead of the status quo model, I followed one of these new models? What would I do differently? How would things change?" This self reflective thought exercise of mindfulness sheds light on the implicit models we use that influence our choices, behaviors, and mental health every day, allowing us to work with them in a healthier way.

In "Life Itself" Rosen wrote "Category Theory comprises in fact the general theory of formal modeling, the comparison of different modes of inferential or entailment structures. Moreover, it is a stratified or hierarchical structure, without limit. The lowest level, which is familiarly understood by Category Theory is, as I have said, a comparison of different kinds of entailment in different formalisms. The next level is, roughly, the comparison of comparisons. The next level is the comparison of these, and so on." (54) In Anticipatory Systems (2nd Ed.) he wrote "The study of models is the study of man. The preservation of models is the preservation of self. A change in models is a change of identity. The identification of one's self with one's models explains, perhaps, why human beings are so often willing to die; i.e. to suffer biological extinction, rather than change their models, and why suicide is so often, and so paradoxically, an ultimate act of self-preservation." (370)

Monkey mind makes mental models

"Monkey mind" is an archetype, a term for the restless, capricious, fanciful, inconstant, confused, indecisive, and uncontrollable characteristics of much of our mental life and inner narrative thought. Our minds tend toward distraction and negligence, anxiety and forgetfulness, leaping from one thought to the next, in short, our minds are often disordered and irrational. And yet despite this, somehow they manage to make sense of things. They produce and interpret coherent narratives. Monkey minds develop, deploy, modify, and use complex models that allow us to anticipate and respond to what is anticipated. Robert Rosen once wrote that modeling is an art, whose essence is the "intuitive leap". If that is true, and complex models rely on the intuitive leap, perhaps we should not grow so impatient and chastise our monkey minds when, from time to time, they seem entirely intractable. For this apparent flaw may also be the source of their greatest strength. Few creatures are more capable of taking great leaps than monkey. Incidentally, Rosen's statement has support from Whitehead, who wrote "Philosophy is the search for premises. It is not deduction. Such deductions as occur are for the purpose of testing the starting-points by the evidence of the conclusions." And from E. O. Wilson, who wrote that the design of models "springs fresh from a more primitive mode of thought, wherein the hunter’s mind weaves ideas from old facts and fresh metaphors and the scrambled crazy images of things recently seen."

Models explaining causality and models describing behavior

Spyridon Koutroufinis: “One way to consider the essential difference between theoretical and systems biology is to make a clear discrimination between two kinds of models. First, there are models for explaining how the behavior of a system is generated. Those models are developed for explaining the internal causality of a system. Newton’s model of the solar system, for example, qualifies as a model that aims at explaining the causal relations between celestial bodies. Second, there are models that aim at describing the known behavior of a system, so that predictions of new behaviors emerging under new conditions can be made. The ancient astronomy that was based on the mathematics of epicycles provided a model describing the behavior of the solar system without explaining the underlying causality (gravitational attraction). Systems biology may content itself with making models that predict the behavior of biological systems in a way that supports the development of new biomedical applications. In contrast, the role of theoretical biology should be to suggest models that explain the causality of organisms.”

Model-Dependent Realism

Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow in "The Grand Design" (page 172) wrote, "Our brains interpret the input from our sensory organs by making a model of the outside world. We form mental concepts of our home, trees, other people, the electricity that flows from wall sockets, atoms, molecules, and other universes. ...The brain is so good at model building that if people are fitted with glasses that turn the images in their eyes upside down, their brains, after a time, change the model so that they again see the world the right way up…” Paul Austin Murphy commented, “Yes, reality-as-it-is-in-itself clearly exists. But that doesn’t mean that we can access (or describe) it as it is in itself. After all, contingent brains (with their contingent “pictures”) and persons are doing the assessing and describing. And precisely because of that, a perfect model or theory will always be out of the question." As Hawking writes, “these mental concepts are the only reality we can know. There is no model-independent test of reality.”

|

| Based on Rosen's fig. in Anticipatory Systems |

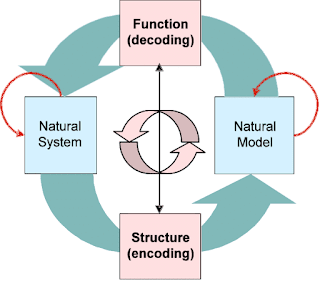

Howard Pattee wrote, “All models are incomplete in the sense that all possible observables cannot be consistently incorporated into a single model. Therefore, we believe in the necessity of multiple alternative models to understand complex systems.” How do these models work? “We encode natural systems into formal models such that the inferences or theorems we can elicit within these formal models become predictions about the natural systems” which can then be verified by further observation. See also these excellent slides by Judith Rosen.

Biosemiotics and Modeling

Arran Gare presented a paper at the annual Biosemiotics Gathering in Moscow this year titled Biosemiosis and Causation: Defending Biosemiotics Through Rosen’s Theoretical Biology. When I realized that few people have taken modeling more seriously than Rosen, who looked deeply into how models allow us to anticipate the future, I decided to read that paper again. Throughout Gare advances his main thesis, which is that Rosen’s work concurs with Peirce’s philosophy and biosemiotics in a number of ways. These two paragraphs really stood out:

It is important to emphasise that Rosen, like Schelling, was totally rejecting Cartesian dualism, so that organism’s ‘ambience’ as he characterized its immediate environment, was not seen as totally separate from it, but as a differentiation within a broader process by which the organism separates itself and maintains this separation within this process, in so doing, dividing the subjective from the objective. To do this, the organism has to maintain a model of itself, again with this model being part of this process while being partially autonomous and having this autonomy maintained. The model as the condition for the organism to differentiate itself from the ambient environment, anticipating developments in this environment and in itself and responding to what has been anticipated, can be conceived as a complex sign facilitating the production of more specific signs involved in a process of distinguishing significant aspects within the organism and within its ambient environment, anticipating and then responding to what is anticipated by constraining activity in the present. Doing so organisms produce chemicals, and beyond this can grow, move, and in some cases, think and engage in critical dialogue. This ‘activity’ involves creating, maintaining, modifying and then reproducing structures which make such semiotic ‘activity’ possible. This ‘activity’ in turn creates, maintains, modifies and reproduces these structures, including codes, cognitive structures and models. What is responded to and to some extent causes the response can be characterized as the ‘Dynamical Object’, following Peirce, but following Schelling, would be better characterized as the ‘dynamical process’, a ‘community of causation’ that includes the differentiation by the organism from its environment and also what is differentiated in this environment.

Human semiosis includes everyday practical activities including transformations of the physical world, the production of goods, speech acts, the production and interpretation of narratives, and the development, deployment and utilization of more abstract models, including mathematical and other scientific models, openning up new levels of freedom. ‘Subjects’ and worlds of Immediate Objects co-emerge with the capacity of organisms for greater anticipation involving more complex models, more complexly differentiated worlds, and greater capacity to respond to what is anticipated, and also a greater capacity to modify their models and their worlds. The development of human culture characterised by ‘with’ worlds (Mitwelten) or life-worlds (Lebenswelten) involving the dialectics of labour, recognition and representation, again being components of each other without being reducible to each other, magnify the possibilities for freedom and creative semiosis. These in turn make possible reflexivity, generating ‘self’ worlds (Eigenwelten) in which people come to understand themselves as individuals living out stories and taking responsibility for themselves and their communities.What models are we transmitting to future generations?

All our vain ambitions to colonize new worlds (which sounds disturbingly all too familiar) will be for naught so long as we ignore the harm we cause to the one we have. Earth’s past, the world we knew, is surely gone. And even the likes of today, as troubled as they are, will not be seen again for a very long time. At this point, all we can do is try to minimize the harm. Reversing it is far more difficult. Perhaps the best thing we can do is pass on the best models we have to help guide future generations in meeting the challenges they will face. They will hopefully take and improve upon these as they are able. Gare put this another way when he wrote "the model of the original organism is bequeathed to its progeny functioning as a sign of the progeny’s environment, and the developing progeny is an interpretant". When I look back at ages gone by, to the thought leaders who came before us, regardless of what other titles and positions they held, I see people who deeply considered the models contemporary to their time and place. People who questioned received wisdom and advanced radical notions, promulgated new ideas, and formulated new models, putting these into practice as best they could. Succeeding generations look back upon them, sometimes with admiration and sometimes more critically.

New models are always a threat to established dogma and ideology. So while Thomas à Kempis didn’t rock the boat when he wrote “The Imitation of Christ”, which was essentially a distillation of the Christian model for life, Baltasar Gracián encountered more resistance with his critical scholarship (he is best known for “Practical Wisdom for Perilous Times”). These authors lived hundreds of years ago. Far more recently, in 1954, Scott Nearing co-authored with his wife, Helen, “Living the Good Life: How to Live Simply and Sanely in a Troubled World”, in which he advocated a modern-day "homesteading” model that has continued to resonate with people today. Today I’m reading “Japanese Philosophy: A Sourcebook”. Within the space of 1340 dense pages it records the evolution of cultural models in Japan. Near the beginning, on page 51, the story of Kūkai is recounted. He “was struck by the alternative model of knowing implied in the esoteric text” of the Mahāvairocana sutra and later went on to found the Japanese Shingon school of esoteric Buddhism. This cemented his reputation and made him arguably the most famous Buddhist figure in Japan... So I ask again: What models are we transmitting to future generations to help guide them in meeting the challenges they will face?

The Nordic Model

In his Op-ed in the New York Times today, Capitalism and ‘Culturecide’, Ai Weiwei writes that "Extraction of profit from slave labor is not new; the main difference today is that the extraction is happening in distant countries." Do the protests in Hong Kong signal a global weakening of democratic values? He suggests they do. Are the concentration camps in Xinjiang supported by global corporations who benefit from the arrangement? He points out that yes, they do. What does this say about our model of civilization? Not so long ago, during the 2016 presidential election, the "Nordic model" of government was frequently brought up. And with Bernie Sanders in the race the for American presidency once again four years later, it may receive the same attention. At that time an article by Ann Jones described it thus: "the Nordic model is a smart and simple system that starts with a deep commitment to equality and democracy. That’s two concepts combined in a single goal because, as far as they’re concerned, you can’t have one without the other." Ai Weiwei's article proves once again that this is more true than any of us likely appreciate. Will we sacrifice our commitment to equality and democratic values in exchange for the illusions of market fundamentalism? I don't think we can afford to. The strengths and weaknesses of our political and economic models will determine whether our values are retained or discarded. Ignoring that relationship comes at too high a cost.

Rom Coles on political philosophy

Having read, just last July, some of Arran Gare’s work (another fine Australian!), I’m reading this article through an interpretive lens consisting, among other things, of various ideas about the function of social models and the 'Deep Social Mind' theory, according to which humans have become cognitively adapted to reflexivity and intersubjectivity. So approaching it from that angle, I think this article does a great job of highlighting the importance of not just understanding how we relate to our models (ecological, political, or otherwise), but also the importance of learning about how other people relate to their models, and crucially putting these two together, discovering how we should relate to each other in light of both their and our models, understanding where these coincide with and diverge from each other. Coles‘ use of the smart grid analogy to illuminate certain aspects of political action that have either been neglected or underused was an inspired choice. And I think it is effective. This might be just the sort of forum conducive to the process of model interrogation Gare and Rosen consider essential for a functioning democracy. Coles writes:

The inferno of the living continues to burn with a fury across the East Coast of Australia, home for tens of thousands of years to Aboriginal peoples. We offer our respect to Elders, past, present and future, who have cultivated countless modes of understanding and living responsively. One of the most vital practices in relational organising is listening carefully to each other share experiences about the challenges created by the dominant political economic order. In this process, we begin not only to understand others. We gain a sense of how others feel the world. What specific issues are making people’s everyday lives unliveable now? (Like buildings that bake people in heat waves, fires that threaten communities, poorer neighbourhoods consistently located in flood zones, myriad aspects of food insecurity, and so on.) ...Instead of being guided so thoroughly by the image of a bullhorn, we might also imagine our actions together as collectively manifesting large, powerful ears, as well. The substantial power of many movements has come in large part from listening attentively to others, as well as from loud dramatic expression. Imagine if, in addition to shouting slogans and “speaking truth to power,” activists sought to create potent performances that engage bystanders, not as a passive audience, but as fellow citizen-participants to be invited, welcomed and curiously engaged in intense — but open-ended and dialogical — dramas around, for example, climate emergency:

* How is it affecting our lives, the places we love, the futures of our children?

* How is this making people feel?

* How might we stop the madness and create a better world together?

|

| Model of depression |

If I ever thought changing my models would be easy or result in immediate observable changes, I was wrong. Why doesn't it? Why is change hard? One reason is because the environment remains the same. New habits need a supportive environment to take root and grow in. Changes in our models require that we make corresponding structural changes in our habits and environments. There is no magic. The same goes for political and economic systems. Recently Warren Buffett said that companies cannot be moral arbiters. Government must create the rules. Business is not about ethics, but about profit. Buffett would have invested in coal if it was profitable. This is, of course, in direct contradiction with most of what corporate America claims. Predictably, their public relations campaign wants to make you think they are a force for good. Plenty of people have been conned into believing that 'free markets' can solve every kind of problem, when in fact they cause many of our biggest issues when not kept in check. There is no magic.

This is related, though somewhat tangentially, to what Jesper Hoffmeyer describes in "The Semiotics of Nature" as "models of embodiment – i.e., models where the bodily anchoring of cognitive or biological functionality are seen as essential to that functionality". As Søren Brier says, we must recognize that the "social and psychological system of emotions, willpower and meaning are just as real as the mechanical system... it is no longer viable to model nature as purely mechanical or mind as only computational". A focus on embodiment, and the connections between emotion and matter, is fertile ground in contemporary scholarship.

In a speech he gave in 1994, Charlie Munger (Warren Buffett’s investment partner) summed up his approach to practical wisdom through understanding mental models by saying: “Well, the first rule is that you can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience both vicarious and direct on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.”

Circular economies presuppose circular models

Jevon's paradox occurs when greater efficiency allows consumption to occur proportional to rising demand. One would think demand would eventually taper and flatten out (however that is highly dependent upon other factors). The problem is consumption and demand, not efficiency per se. Consumption can partially be addressed through material substitutions (for example, dietary choices). And demand can be addressed through natural demographic transitions and better models that couple the human system with the greater system it lives within: the environment. We need more interconnected models for all aspects of society (economic, resource use, education, etc.). So while efficiency and resource substitutions can prolong economic growth and reduce its environmental impacts, what we would benefit from most is better modeling, which illuminates how limits are an inherent part of any particular system. All systems have limits, they just draw them differently. And of course, our current human-planet system is breaking down due to exceeding the limits we blithely ignore, even at the highest levels of governance. The challenge is to design a closed-loop system that will allow a high quality life for all members of our ecosphere without exceeding system limits. Any system model that is unable to close the information loop on reality has absolutely no hope of closing the physical loop on energy and materials.

As Michael Braungart and William McDonough wrote on the subject of industrial ecology: “Human beings don’t have a pollution problem; they have a design problem. If humans were to devise products, tools, furniture, homes, factories, and cities more intelligently from the start, they wouldn’t even need to think in terms of waste, or contamination, or scarcity. Good design would allow for abundance, endless reuse, and pleasure.” That's the techno-utopian idea in a nutshell, focused on closing the physical loop. But again, implicit to that perspective is the requirement to close the information loop on reality. The "design problem" Braungart and McDonough described is really a "modeling problem" for closing the information loop: How do you model the human and ecological subsystems such that they provide quality within system constraints? First things first, check to ensure your information feedback loop is closed, both Robert Rosen and Hugh Dubberly have emphasized this precondition.

Intentional communities and virtual communities

Ecovillages, like Dancing Rabbit, or "transition towns" are intentional communities formed with the purpose of living in greater harmony with the environment. They seek to couple the human system with the greater system it lives within. The basic model of an intentional community has been around for centuries, however promoting local and global sustainability as their primary focus is a more recent development. According to the theory, you can more quickly and easily develop sustainable modes of living if you eliminate the sources of systemic resistance to environmental action by living in a cooperative arrangement with like-minded people. I like this idea very much; it is a good model and has worked for many people. But it hasn't caught on quickly enough and I think it is important to ask why. I also think that we need to identify possible alternatives that might help speed progress to the same goals. What I'd like to propose is a "virtual transition town" model (I can't be the first to have proposed this). We could create a virtual community center that combines the enormous resources of many distributed homes. Think of it as a virtual intentional community or ecovillage. This kind of networking has already been successfully tried in a few well-defined situations, and a few businesses have grown by leveraging peer-to-peer networks in similar ways. The early growth of e-commerce saw Ebay, then Craigslist, and now Facebook marketplace. What you can't get from them you can order from Amazon with free shipping. But none of these business models incorporate environmental responsibility, the core value of ecovillages, into their models.

What we need is a local, distributed, and publicly owned "Amazon fulfillment center", a virtual warehouse with an online searchable database. With this we can pool local talent and resources for community use. Although different, this is the same basic model that used bookstores, tool libraries, "free stores", and second hand economies of reuse are built upon. This is what advocates of a "circular economy", industrial ecology, and economic degrowth have been promoting. Maybe this would look something like Craigslist, but with democratically agreed upon measures of sustainability built into a voluntary system to promote greater community health. For many reasons, joining or forming an intentional community may not be an option for many people, but maybe we can create an equivalent model that can help bring the ecovillage dream to them, without sacrificing the local networks they have already developed. If it is to work, just like an ecovillage itself, it has to be a group effort.

Models for energy, housing, and community spaces